Supply and demand have been extremely volatile over the past 12 months.

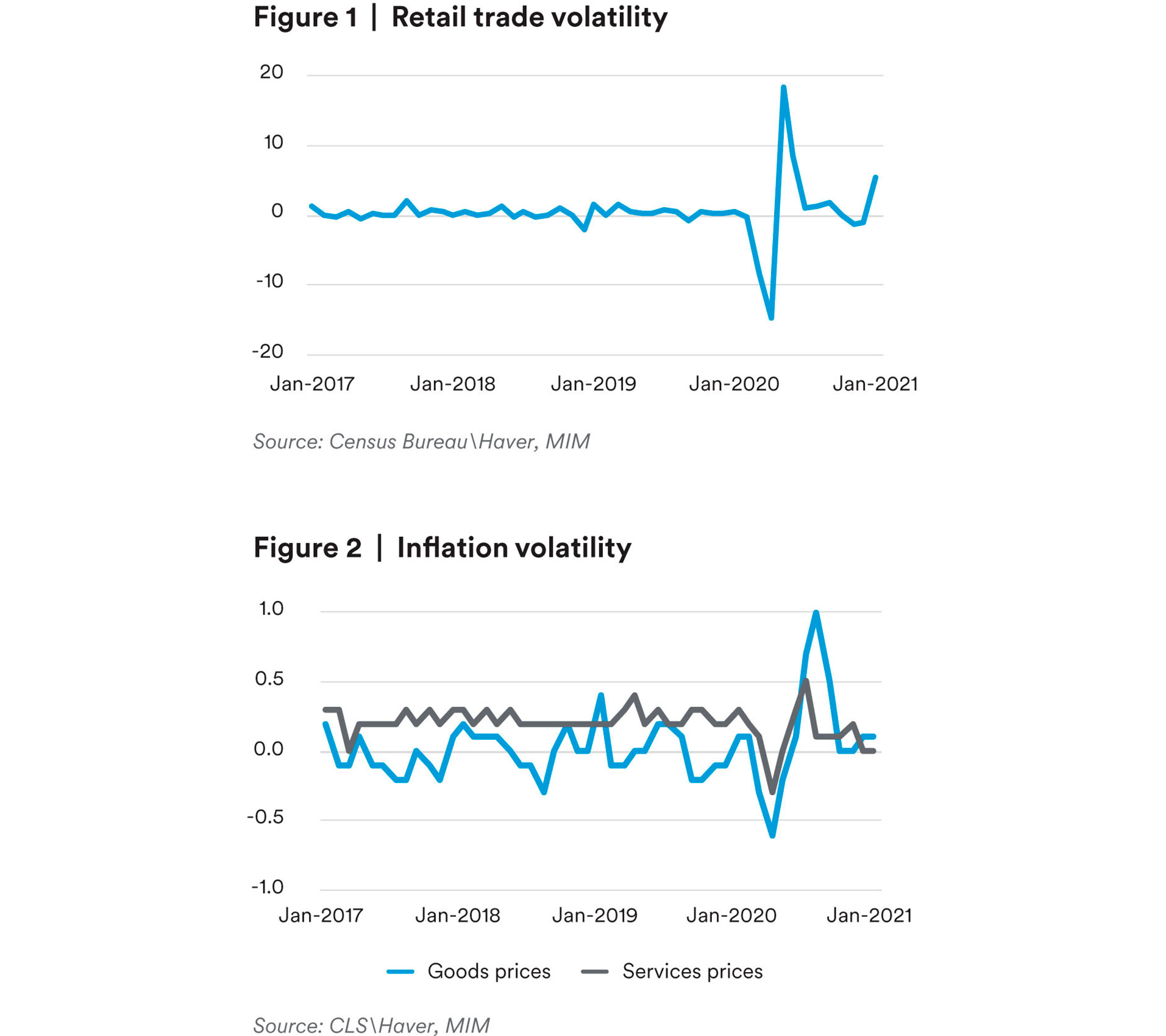

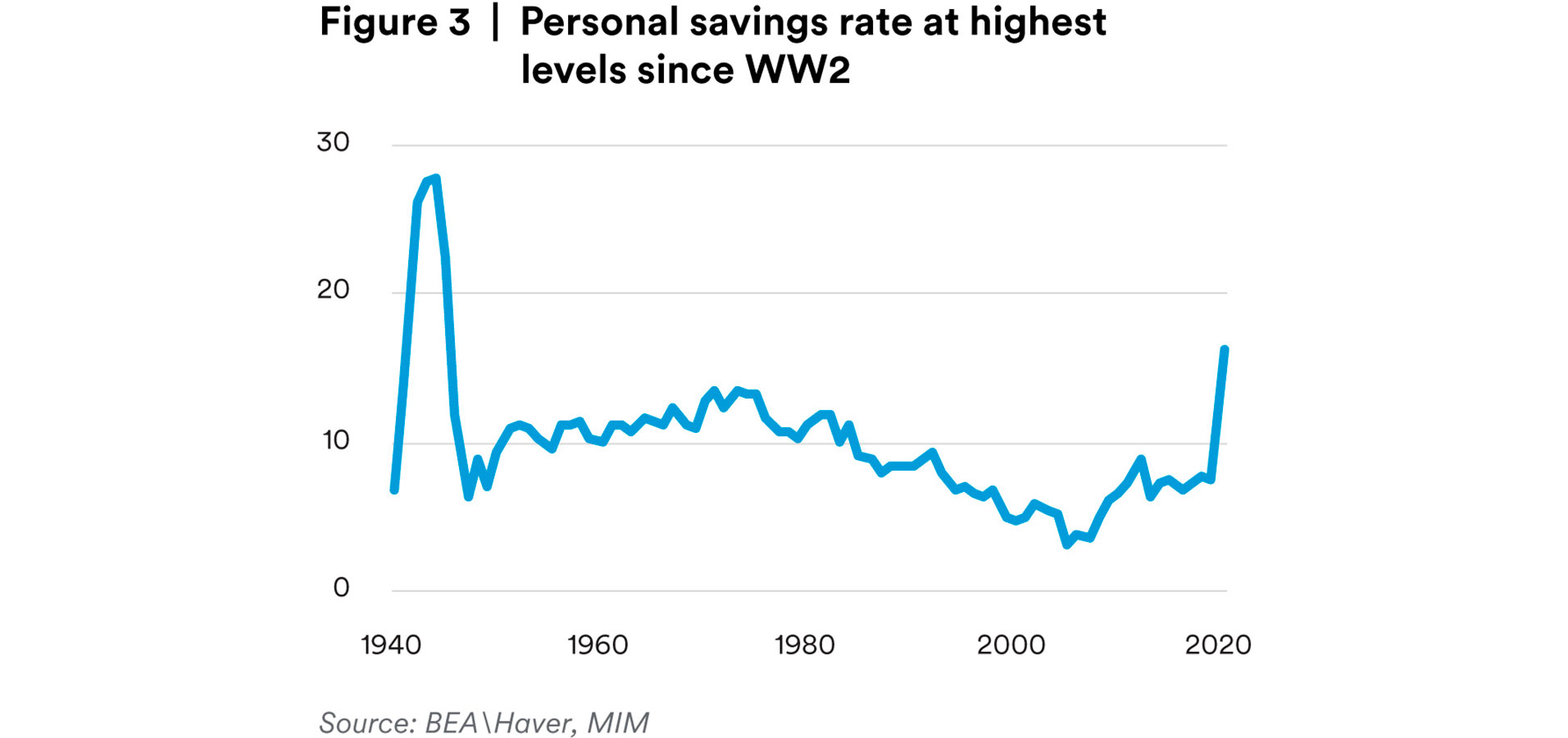

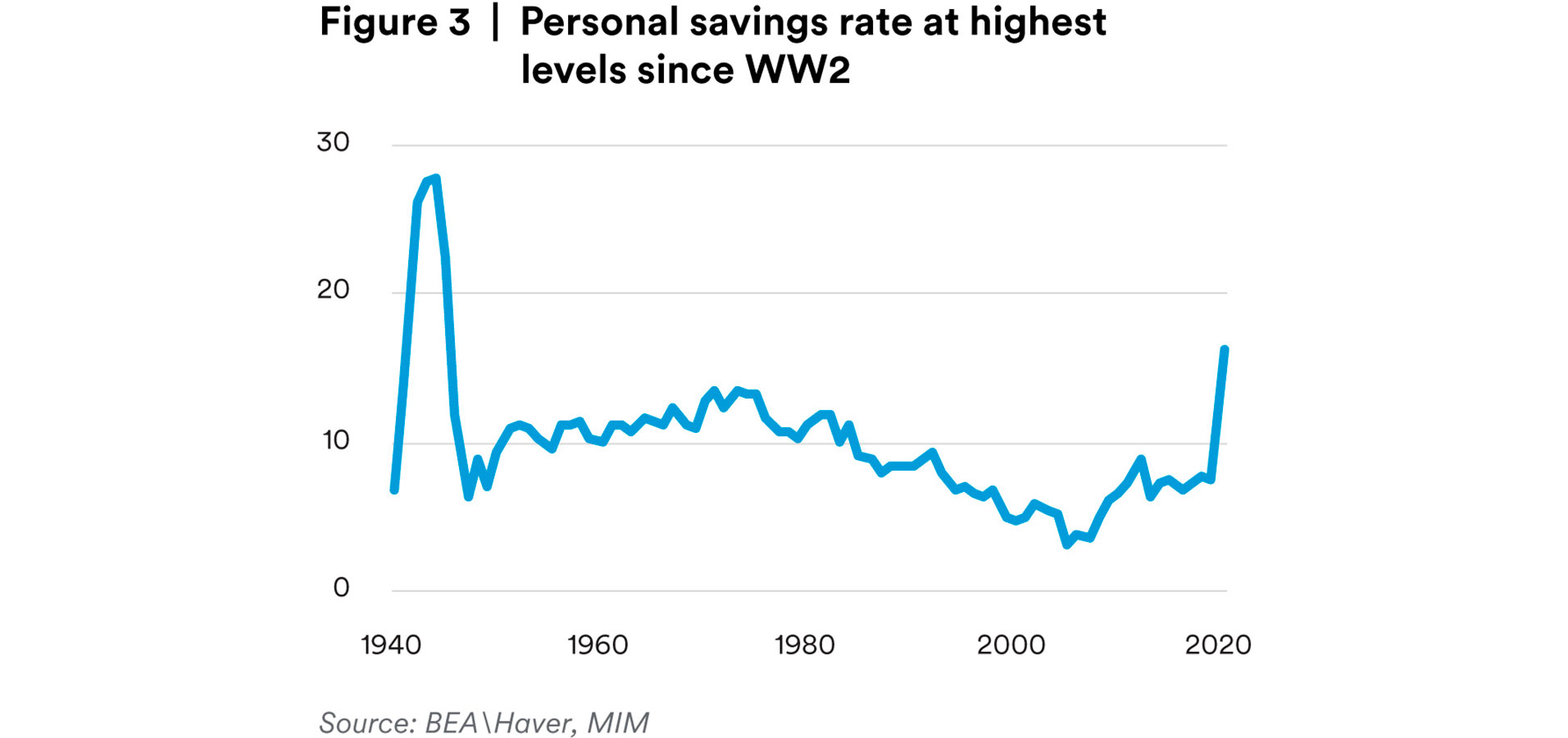

From toilet paper at the beginning of the pandemic to used cars mid-pandemic to semi-conductor shortages most recently, the pandemic economy has been plagued by shortages. Production has been constrained due to COVID-19 induced closures, social distancing requirements on production lines, and worker sickness. Consumers have altered their spending patterns drastically, changing both the types of products demanded and the way they are purchased. Figures 1 and 2 show the increase in volatility in both products demanded and prices.

One example of how this instability is still currently affecting the economy is the global semiconductor shortage. This shortage has reportedly been caused by pandemic-related demand shocks, a changing U.S. trade policy, and lean supply chains.1 The chip shortage may result in additional months of downstream supply trouble including for consumer goods (e.g. gaming equipment and automobiles) and capital equipment (e.g. production line machines).2 The latter may induce further downstream effects.3

Another example is in lumber, stemming from the housing boom that has taken place during the pandemic and constraints to lumber mill capacity.4 This appears to also be related to another common phenomenon, COVID-related constraints on worker proximity leading to less effective production capacity.

Such shortages highlight the continuing vulnerability of efficiency-optimized supply chain in extraordinary times. Supply chains remain under stress and are likely to continue to have less buffer than usual to withstand any unexpected stresses, such as the February 2021 Texas snowstorm.5

How will the rest of the year go?

Going forward, economic volatility ought to decrease relative to the height of the pandemic. We expect the economy to move mostly in a positive direction. The supply chain problems noted above are likely to improve as people shift from goods to services consumption. But the economy has been knocked off its moorings; a picture of the “new normal” is still unclear, and how we get there is equally unclear. We expect at least some volatility to continue as producers and consumers search for equilibrium.

Consumption recovery may take time

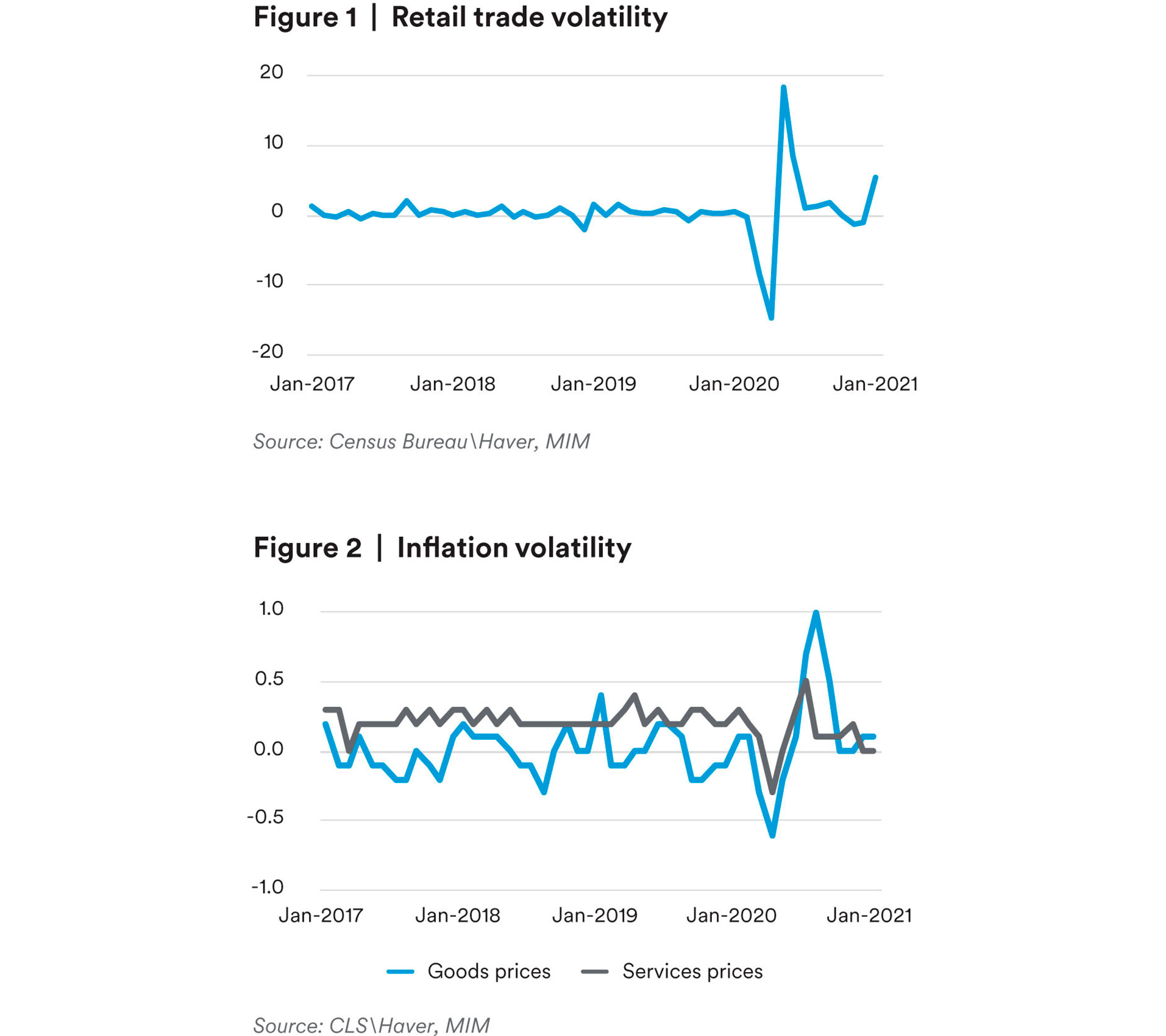

Consumers, despite having accumulated a war chest of savings (double the pre-pandemic savings rate),6 may initially be reluctant to start spending. There are many examples where consumer spending has taken time to resume.

Israel has been leading the world in vaccinations, and on February 21, 2021 reopened much of its economy including shopping malls and markets.7 It is too soon to tell definitively how strong the response, but the first few weeks indicate that Israelis have resumed pre-pandemic levels of necessity shopping (e.g. groceries) but retail, recreation and public transportation remain nearly 30 percent below pre-pandemic levels.8

China has experienced one of the strongest rebounds globally. Much of the growth has come from the production side, which the government has more heavily supported. Despite the support, companies have not fully bounced back, with the job market presenting some continued weakness. This has translated into a sluggish consumer spending recovery.9 Savings rates also appears to remain high as the greater uncertainty may be leading people to save more.

Other moments of U.S. history have also shown somewhat sluggish spending recoveries. During World War 2, consumers were restricted from buying due to government-imposed rations. Savings rates peaked in 1944 at 27.9 percent of disposable income; it took until 1947 for savings to revert to more usual levels.10 2020’s personal savings rate of 16.4 percent is the highest rate since.

One final example comes from the September 11th, 2001 terror attacks, after which air travel saw a substantial loss of demand. It took as many as seven years for demand to fully return.11 (See Metlife Investment Management Recovering Consumer Confidence: Lessons From September 11.)

Similar effects could linger the pandemic. Over the past year, people may have been conditioned to think of certain activities like going to the doctor, going on a cruise, buffets, or going to the spa as high risk and to be avoided. A sort of “scarring” may occur in response to the realization that pandemics and other rare events could occur, which could translate into consumers not spending down their savings all at once.12 Even if the behavior is not permanent, there is likely to be a transition period.

Producer constraints and trial and error

Producers face multiple problems. The first is their own supply constraints, including bankruptcies and supply chain pressures. Second, producers face the daunting task of trying to forecast consumer demand in the new normal. How well firms can anticipate their consumers’ post-pandemic behavior will determine a lot about how much economic activity will flourish.

Pandemic-related damage to the supply side is a concern. Recovery comes too late for many businesses, particularly restaurants and other local businesses, with thousands of small businesses closed down for good.13 New businesses will surely be founded, but this will take time, and in the meantime certain areas may face a shortage of local businesses.

Bankruptcies of large corporations are at their highest level since the 2008 financial crisis.14 Notwithstanding the fact that we expect bankruptcies to resolve themselves fairly rapidly relative to 2008,15 it will take some time for sectors – the energy sector, the airline sector, retail – to re-orient themselves. Dissolution of some major businesses, and the layoffs they entail, will take time to resolve as consumers and producers figure out winning formulas for the new normal.

Figuring out consumer demand patterns in the new normal is a puzzle that producers need to solve. Some unknowns that producers are grappling with include:

- How have preferences shifted in the last 12 months? Both with respect to types of goods and services and with respect to how purchases are made and received (online, curbside, a return to in-store buying).

- How will the geography of consumption patterns change? With many people moving during the pandemic, and with the possibility of continued remote work for some white-collar jobs, are surrounding and related businesses in the right locations?

- How much progress will Europe, Japan and China make in their recoveries, and what does this mean for demand for U.S.-made exports? Will there be any lingering negative effects on imports?

- How will consumers respond to the next stimulus bill that is likely to be passed? Where and when will that money be spent?

The answers will take time to develop. The hints from recent surveys of consumer behavior point to enormous upheavals in consumer behavior. Some retailers are bracing for an expected slowdown in demand and a continued shift to online purchasing, while others are betting on a continued uptick.16 Directly surveying consumers appears to show large professed changes in expected behavior post-pandemic.17 McKinsey surveys show a strong tilt toward sticking with new behaviors: for example 73 percent of people have tried new brands, of whom 60 percent expect to keep buying those new brands, while large fractions of the population intend to keep buying online across almost all product categories post-pandemic.18 Accenture believes home goods will remain a trend post-pandemic,19 while others forecast a run on services.20 A YouGov-Cambridge Globalism Project survey showed that people expect to continue to drive more post-pandemic, rather than using public modes of transportation (including airplanes).21 A PwC poll of CFOs showed that 63 percent of firms are expecting to change their products or services to respond to changes in demand. Firms are attempting to deploy technology to both determine new consumer habits and to meet them.22

The changing location of demand may be somewhat less dramatic. Some share of white-collar workers is expected to initially keep working from home at least part time. It’s unclear how long lasting this trend will be, and we expect the trend would eventually revert back to more people back in offices full-time.23 (see Metlife Investment Management The Pandemic Pitfall: Short-Term Forecasts Could Drive Mispricing in U.S. Office.) However, in the near term this could affect the recovery of restaurants and other stores and services in cities’ business districts.

Finally, consumer preferences are likely a moving target. Just as after September 11th, consumers migrated from a position of fear and aversion to flying to full recovery over a period of about seven years, so too do we expect consumers’ preferences to evolve from the initial new normal (which we expect to see emerge this year) to a state in which consumers are more comfortable with the post-pandemic reality, perhaps even forgetting or discounting some of the pandemic lessons. Although this evolution will likely play out after 2021, it is yet another variable that producers will need to consider as they adapt.

A rocky recovery path

Consumers and producers are facing a substantial reconstruction effort. A number of issues are likely to stand in the way of a smooth recovery. Consumers are likely to hesitate to spend their accumulated savings all at once. Many companies are likely to make incorrect forecasts about their consumers. The pandemic may take a longer – or shorter– time to get under control than either consumers or producers expect.

We expect the U.S. economy to grow – and grow rapidly – in 2021. But we expect the ride to be quite rocky, and the forecast to be more uncertain than usual.

Endnotes

1 “A Year of Poor Planning Led to Carmakers’ Massive Chip Shortage,” Debby Wu, Gabrielle Coppola, and Keith Naughton, Bloomberg, January 19, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-19/a-year-of-poor-planning-led-to-carmakers-massive-chip-shortage

2 “The World Is Short of Computer Chips. Here’s Why,” Debby Wu, Sohee Kim and Ian King, Bloomberg, February 17, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-17/the-world-is-short-of-computer-chips-here-s-why-quicktake

3 A current example using the global semiconductor shortage is that chip shortages could result in automakers foregoing sales of $61 billion in Q1 2021. “The World Is Short of Computer Chips. Here’s Why,” Debby Wu, Sohee Kim and Ian King, Bloomberg, February 17, 2021.

4 “The shortage causes, outlook, and what you can do in the meantime,” Jessica Franchuk, Construction Magazine Network, December 28, 2020. https://www.constructionmagnet.com/news/the-2020-lumber-shortage

5 The Texas snowstorm also had knock on effects into the downstream petrochemicals markets. “U.S. freeze chills Asian plastic makers as feedstocks soar,” Saket Sundria and Jack Wittels, Bloomberg Markets, February 23, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-23/u-s-freeze-chills-asian-plastic-makers-with-feedstocks-soaring

6 BEA\Haver

7 “Israel’s speedy vaccination campaign now faces key test in returning to normal,” Felicia Schwartz, Wall Street Journal, February 21, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/israels-speedy-vaccination-campaign-now-faces-key-test-in-returning-to-normal-11613929717

8 Google Mobility data as of March 7, 2021.

9 “China’s economy isn’t out of the woods, despite a strong 2020,” Stella Yifan Xie, Wall Street Journal, February 7, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-economy-isnt-out-of-the-woods-despite-a-strong-2020-11612710000

10 U.S. Dept of Commerce\BEA\Haver.

11 ”Recovering Consumer Confidence: Lessons Fromm September 11,” Metlife Investment Management Insight, May 1, 2020.

12 “Scarring body and mind: the long-term belief-scarring effects of COVID-19,” Julian Kozlowski, Laura Veldkamp, and Venky Venkateswaran, NBER Working Paper Series, WP27439, June 2020.

13 “Yelp: Local Economic Impact Report,” Yelp Economic Average, September 2020.

14 “Pandemic spurs most bankruptcy filings since 2009,” Jeremy Hill and Katherine Doherty, Bloomberg News, January 5, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-05/u-s-bankruptcy-tracker-pandemic-spurs-most-filings-since-2009

15 “Zombies at Large? Corporate Debt Overhang and the Macroeconomy,” Oscar Jorda, Martin Kornejew, Moritz Schularick, Alan M. Taylor, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, Staff Report No. 951, December 2020.

16 “Best Buy Tests its Luck,” Jinjoo Lee, Wall Street Journal, February 25, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/best-buy-tests-its-luck-11614270609?mod=searchresults_pos1&page=1

17 “China’s inflation divergence shows unbalanced economic recovery,” Bloomberg News, February 9, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-05/u-s-bankruptcy-tracker-pandemic-spurs-most-filings-since-2009

18 “The quickening,” McKinsey Quarterly – Five Fifty, July 2020; “Consumer sentiment and behavior continue to reflect the uncertainty of the COVID-19 crisis,” McKinsey – Our Insights, October 26, 2020.

19 “COVID-19 has triggered an ‘enduring focus on the home’, says expert,” Kacey Culliney, Cosmetics Design, February 4, 2021. https://www.cosmeticsdesign-europe.com/Article/2021/02/04/Post-COVID-consumer-trend-of-more-focus-on-home-to-last-10-years-says-Accenture

20 “After the Covid Pandemic, a Surge in Demand for Meals, Entertainment and Vacations,” Justin Lahart, Wall Street Journal, February 5, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/after-the-covid-pandemic-a-surge-in-demand-for-meals-entertainment-and-vacations-11612521000

21 “People plan to drive more post-Covid, climate poll shows,” JonthanWatts, The Guardian, November 10, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/nov/10/people-drive-fly-climate-crisis-global-poll-green-recovery-covid-pandemic

22 “Ending the retail apocalypse and the next era of post-pandemic retail innovation: insights from IKEA’s Chief Digital Officer,” Brian Solis, Forbes, February 23, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/briansolis/2021/02/23/ending-the-retail-apocalypse-and-the-next-era-of-post-pandemic-retail-innovation-insights-from-ikeas-chief-digital-officer/?sh=1ef1916b460f

23 “The Pandemic Pitfall: Short-Term Forecasts Could Drive Mispricing in U.S. Office,” Metlife Investment Mangement, November 16 2021.

Disclosure

For Institutional Investor, Qualified Investor and Professional Investor use only. Not for use with Retail public.

This document has been prepared by MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”) solely for informational purposes and does not constitute a recommendation regarding any investments or the provision of any investment advice, or constitute or form part of any advertisement of, offer for sale or subscription of, solicitation or invitation of any offer or recommendation to purchase or subscribe for any securities or investment advisory services. The views expressed herein are solely those of MIM and do not necessarily reflect, nor are they necessarily consistent with, the views held by, or the forecasts utilized by, the entities within the MetLife enterprise that provide insurance products, annuities and employee benefit programs. The information and opinions presented or contained in this document are provided as the date it was written. It should be understood that subsequent developments may materially affect the information contained in this document, which none of MIM, its affiliates, advisors or representatives are under an obligation to update, revise or affirm. It is not MIM’s intention to provide, and you may not rely on this document as providing, a recommendation with respect to any particular investment strategy or investment. The information provided herein is neither tax nor legal advice. Investors should speak to their tax professional for specific information regarding their tax situation. Investment involves risk including possible loss of principal. Affiliates of MIM may perform services for, solicit business from, hold long or short positions in, or otherwise be interested in the investments (including derivatives) of any company mentioned herein. This document may contain forward-looking statements, as well as predictions, projections and forecasts of the economy or economic trends of the markets, which are not necessarily indicative of the future. Any or all forward-looking statements, as well as those included in any other material discussed at the presentation, may turn out to be wrong.

Unless otherwise noted, none of the authors of the articles on this page are regulated in Ireland.