Introduction

Since the twin crises of the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many have become worried about the future of globalization and its vulnerability from both a supply-chain and a geopolitical perspective. There has been much talk about reshoring, nearshoring, friendshoring and deglobalization. Individuals, companies and governments have seen the fragility of global interconnectedness.

Globalization in the 21st Century

Globalization in the 21st century until the COVID-19 pandemic can be roughly divided into two phases: one of a robust expansion of global trade and financial flows, and widespread policy support for globalization, and a second phase of consolidation and weaker policy support.

Phase One: China’s Accession to the WTO

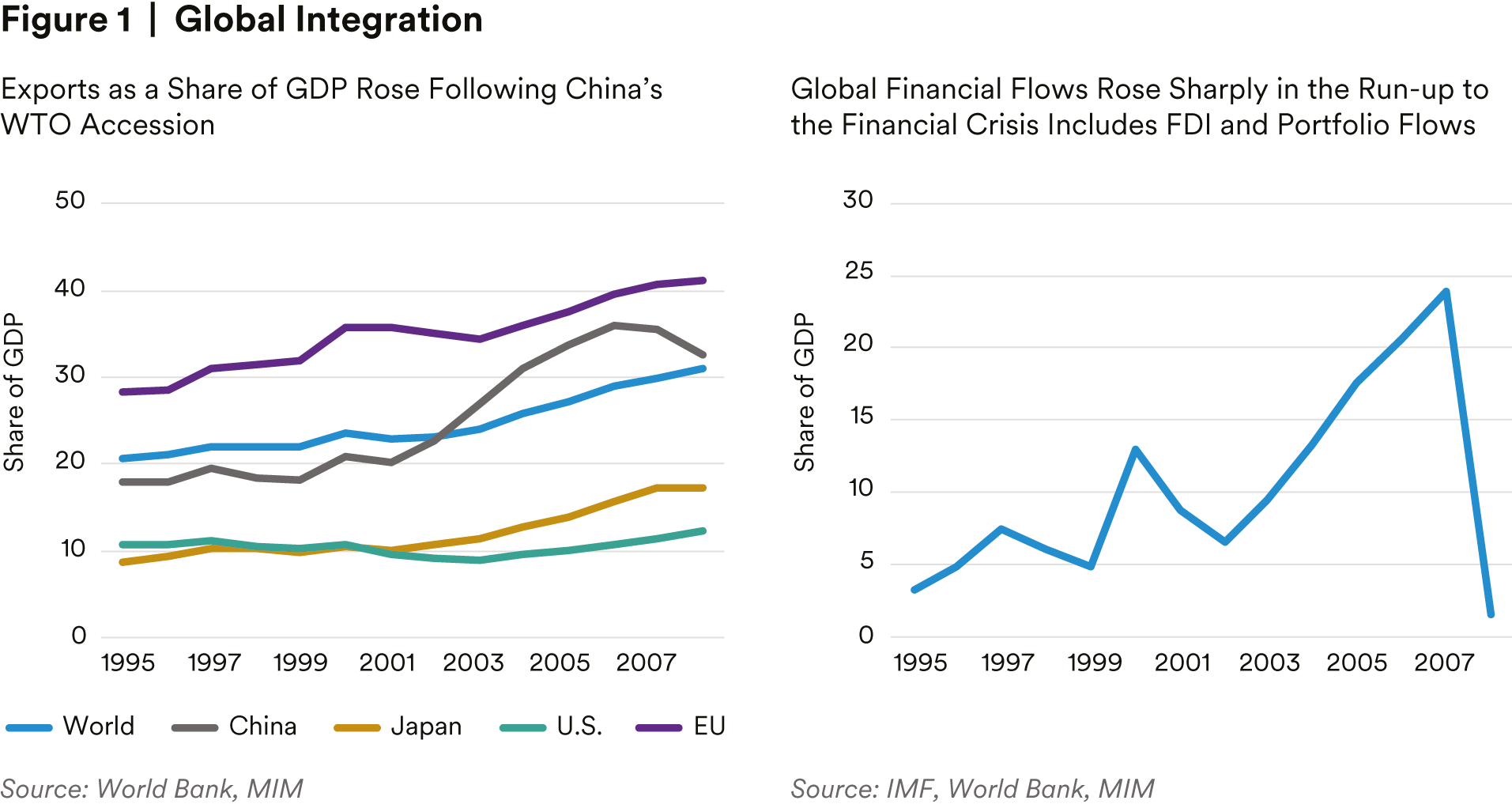

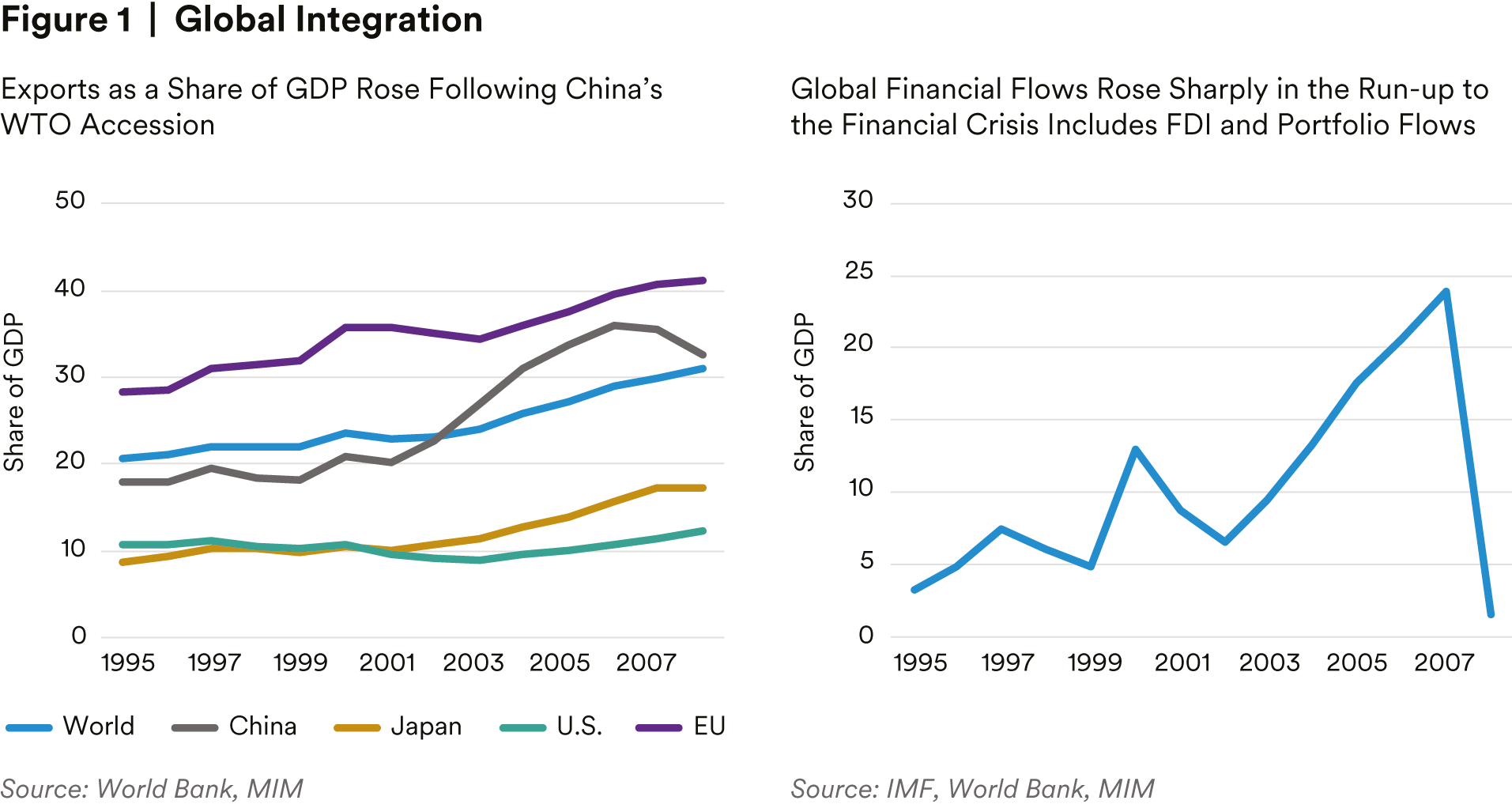

First came a boom in global trade after China entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. This phase was marked by a rapid increase in global trade and financial flows (Figure 1). China was on the receiving end of substantial investment as global firms invested in the “factory of the world” and integrated China into efficiency-maximizing supply chains. Exports from China, the European Union (EU), Japan and the United States all grew from China’s WTO accession to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Financial flows expanded rapidly until the shock of the GFC.

At the policy level, the U.S. engaged in a flurry of international trade negotiations, entering or signing 11 agreements between 2001 and 2008. Japan signed nine economic partnership agreements over the same period, mostly with regional partners. The EU focused on expanding its membership to include an additional 12 Eastern and Southern European countries between 2004-07, taking its total membership to 27 countries. Multilateral engagement continued with the inception of the Doha Round of WTO negotiations in 2001.

Phase Two: Post-GFC Consolidation

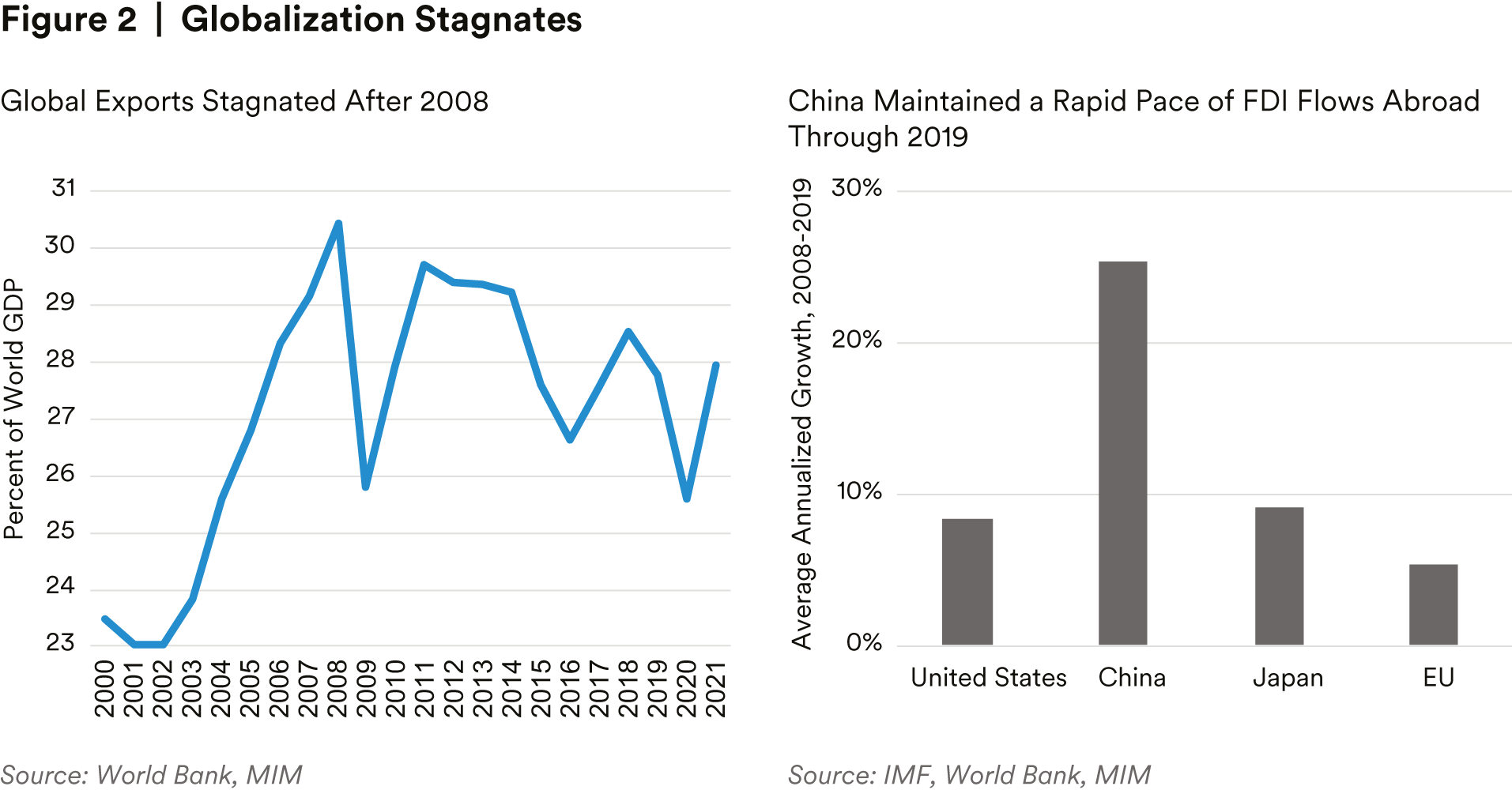

Globalization started to mature after the 2008 financial crisis. International economic activity began to plateau, and policy negotiations around large, multilateral trade agreements became more contentious. Instead, trade agreements advanced more at the regional rather than global level.1

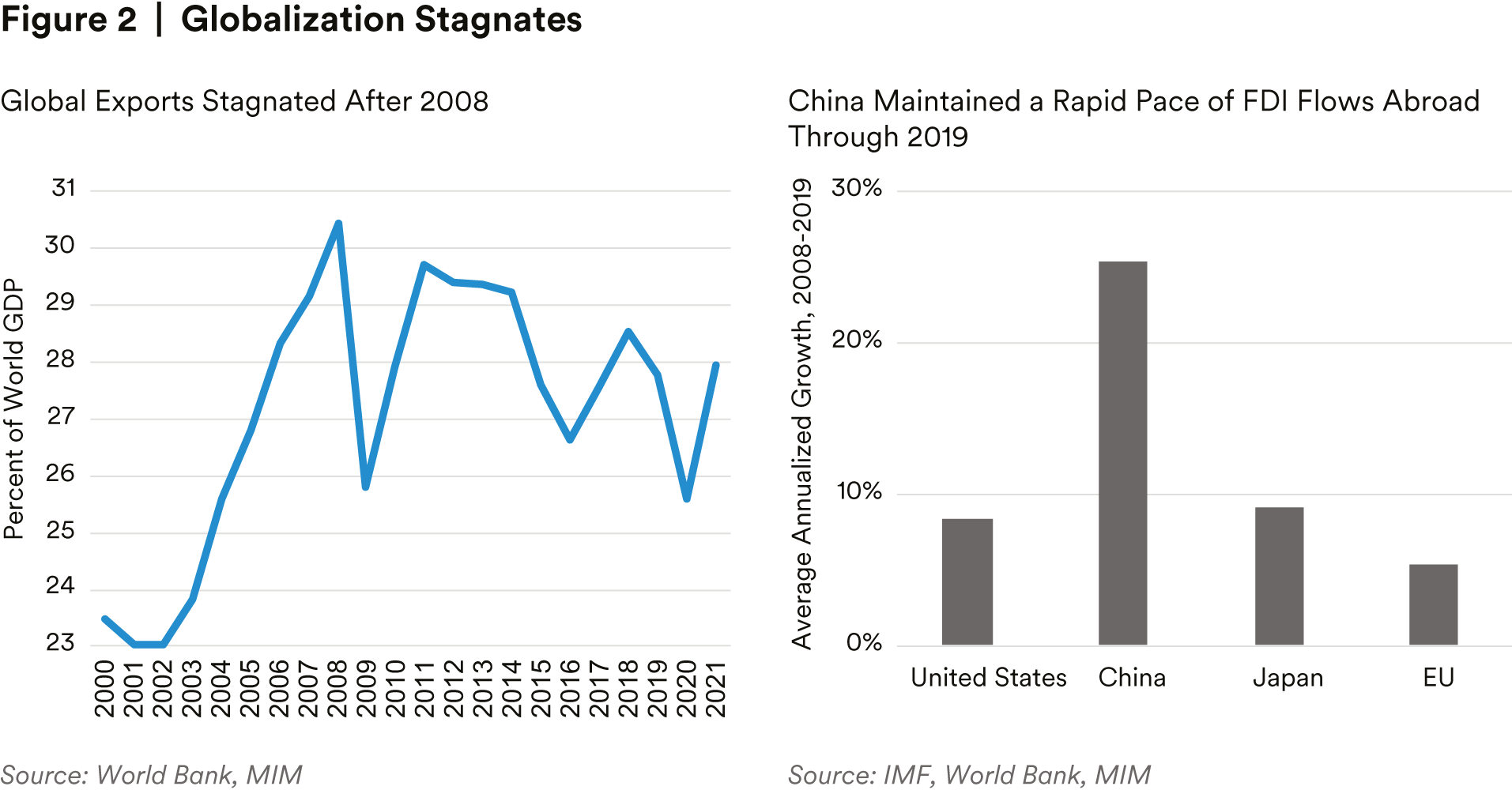

Trade growth moderated following the financial crisis, no longer consistently outpacing GDP growth (Figure 2). Growth in FDI flows was similar for major economies, with China being the exception both as a recipient and—increasingly—as an investor abroad.

Cooperation between Europe and China continued, with many EU member states joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and select EU member countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). EU trade with China increased between 2008 and 2019. Emerging markets also continued to build on their relationship with China. As an example, in 2019, 24% of South American exports went to China, and 13% went to the United States. This is a reversal of the relationship that existed in 2008, when 21% of South American exports went to the U.S., and 8% went to China.2

The assumptions around the benefits of globalization were increasingly questioned. Interest groups such as labor unions and environmental groups across developed economies began to successfully integrate their agendas into trade agreements.3 This joined increased concerns about globalization in emerging economies.After a series of annual negotiations starting in 2001, the Doha Round collapsed in 2008 on the basis of emerging markets’ concerns about the implications for agriculture, foreclosing hope of a new multilateral trade agreement.4 The EU received a blow when the U.K. voted to leave in 2016. Aside from shrinking its own free trade area, Brexit meant that the EU lost a strong voice for free trade.5

During this period, EU policy began to exhibit some ambivalence about the future of globalization. The EU initiated the Europe Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI)—and its eventual successor InvestEU—the goal of which was to improve domestic European competitive capacity with an eye toward reducing trade dependence. At the same time, however, the EU did continue to pursue free trade policy, as it increased its external trade negotiating activity and signed seven agreements of various types.

Aside from the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), an update to NAFTA signed in 2019, the U.S. did not conclude any other free trade agreements during this phase.6 In fact, the U.S. began to undertake a more apprehensive approach to trade. When talks began on the 12-nation TransPacific Partnership (TPP) in 2008 under President George W. Bush, the explicit goal of the U.S. for the TPP was to ensure that “the United States—and not countries like China—are writing this century’s rules for the world’s economy.”7 However, by the time of the 2016 presidential election, trade agreements had become so politically toxic that both presidential candidates vowed to withdraw the U.S. from the TPP. The agreement was eventually signed by all participants except the U.S., was renamed the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and excluded several provisions of particular interest to the U.S.8

Under President Trump, the U.S.’ trade policy became substantially more skeptical. In 2018, the U.S. imposed tariffs on aluminum, steel, washing machines and solar panels from a number of its trade partners including the EU, India, Canada and China. Each of these partners responded by imposing tariffs on imports from the U.S. Later that year, the U.S. added tariffs to an array of Chinese exports, with the stated goal of punishing China for intellectual property theft. China retaliated with its own set of tariffs. Beyond tit-for-tat trade measures, the U.S. also withdrew from or even weakened some international institutions and norms governing global trade—for example, when it blocked the nomination of new judges to the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Appellate Body. This weakened the WTO’s ability to deliver binding decisions on cases brought before it.

Japan continued to engage globally during this phase. It signed another eight economic partnerships and participated in TPP negotiations with the U.S. It also joined China in discussions over China’s proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), in large part to prod U.S. negotiations on TPP toward Japanese interests.9

For its part, China became substantially more active on the global stage: in addition to the RCEP, it founded the BRI in 2013 and the Beijing-based AIIB in 2016. Each of these initiatives had the goal of giving China more of a voice in international rulemaking around newer trade (CBAM), which seeks to put a “fair” price on emissions created during the production of carbonintensive goods in third countries when those goods are imported to the Union. While positive from an ESG perspective, we see the green transition and related market distortions created by policies like the IRA and CBAM threatening to materially increase barriers on free trade and contravene existing international trade agreements and norms as countries compete via subsidies and interventions. topics such as digital trade, and some older topics such as trade in services, investor-state dispute settlement and intellectual property rights.10

The Current State of Globalization

The world’s economies are still trying to absorb the twin lessons of the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. There is increased anxiety about supply chains in the wake of both shocks, and increased attention on what steps need to be taken to create more secure supply chains. There is particularly anxiety about energy security, both in the near term with respect to the Russia-Ukraine war and the longer term around the energy transition away from fossil fuels. Finally, there is anxiety around the stability of geopolitical relationships that underpin international economic relations.11

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has led European countries to seek energy independence from Russia and rethink both their energy sourcing and industrial base. Indeed, there are already some factories being shifted away from Europe to locations in China.12 Meanwhile, the passing of the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has raised concerns that the subsidies it includes will disproportionately attract new “green” investments to the U.S. and has triggered calls in Europe and elsewhere for countries to increase state subsidies and government intervention to counter those provided in the IRA. Moreover, the EU continues with plans to introduce a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which seeks to put a “fair” price on emissions created during the production of carbonintensive goods in third countries when those goods are imported to the Union. While positive from an ESG perspective, we see the green transition and related market distortions created by policies like the IRA and CBAM threatening to materially increase barriers on free trade and contravene existing international trade agreements and norms as countries compete via subsidies and interventions.

The political relationship between the U.S. and China has become more tense, as supply chain concerns, particularly in the technology space, have accelerated the U.S. shift away from China. During the pandemic years, the U.S. introduced several protectionist policies via the CHIPS and Science Act. Although some, such as building a semiconductor fabrication plant in, or blocking exports of semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China, are arguably matters of national security, others, such as providing solar panel production subsidies, are more firmly industrial policy. The U.S. has also persuaded the Netherlands and Japan to restrict exports of the most cutting-edge chip-making equipment.13 The U.S. also set up the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), an Asian-focused framework meant to counter China’s influence in the region; however, this is very different from traditional free trade agreements, lacking their economic heft and setting aside the integration between Latin American and Asian countries that the CPTPP has.14

For its part, China continues to engage globally, despite its self-imposed isolation during its zeroCOVID policy. In 2021, it introduced its Global Development Initiative (GDI), an initiative that has not yet been fully articulated, but is broader in geographical scope than its other initiatives like the RCEP and BRI. It has also applied to join the CPTPP, which would convert the U.S.-initiated regional trade agreement into a China-influenced one.

Where is Globalization Headed?

The global economic order appears to be at the beginning of a new phase. We see three plausible themes going forward, each of which has a chance to become the dominant path over the next several years.

Disengagement

Under a disengagement scenario, the U.S. would withdraw from global economic leadership. This would effectively be an acceleration of the trend in policies seen since 2016 and enhanced of late with measures like the IRA: protecting domestic producers with tariffs and conducting industrial policies that favor select sectors. The U.S. would continue to weaken WTO norms around trade remedies (the EU, for example, claims that the IRA contravenes WTO rules). Disengagement with China would accelerate, and we could see a “light” version of disengagement with Japan, the EU and other trade partners as the U.S. continues to pursue its domestic industrial policy priorities.

If the U.S. were to continue to step back further from global leadership, China would be well positioned to fill the resulting leadership vacuum. This would also be consistent with recent initiatives by China, such as the RCEP, BRI and GDI, to increase its influence over international rulemaking.

De-dollarization, particularly via a shift toward the yuan as a means of international transactions, would be a concern in this scenario. Certain pieces have already been put into place by China, including the digital yuan, the establishment of the Cross Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) in 2018 and the opening up of China’s bond markets to international investors. These all play a longer-term role in a future where the yuan is a viable alternative international currency.

In this scenario, we could see the EU decline to fully follow the U.S. on an aggressively protectionist agenda; most EU economies are heavily geared toward trade. Moreover, in a disengagement scenario, European leadership would try to retain their strong commitment to global engagement, including engagement with China.15 However, as in the U.S., there are political pressures to engage in industrial policy and protective measures for the home economy, and European nations could still be pulled into various components of the U.S. shift against China, such as it was in the blocking of the export of semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China.

Economically, this could lead to a sharp decline in U.S. productivity as it attempts to bring more parts of the supply chain home. Lower trade intensity and lower FDI are associated with lower productivity growth. It could lead to a loss of competitiveness by U.S. firms as international trade rules are shifted away from protecting intellectual property rights (a strength of the U.S.) and toward China-favoring economic conduits like state-owned enterprises. By contrast, it could help improve the relative position of Chinese, Japanese and European firms as they work together to fill the void left by U.S. firms.

Division

Another possible scenario is a two-poled world split between the U.S. and China, fragmenting supply chains and economic relationships. We would expect the economic contest to be between the existing trade rules and order, on the one hand, and a more China-influenced trade regime on the other.16

The EU and Japan’s actions would be a key differentiating feature between a disengagement scenario and a division scenario. A division scenario would need to see the EU and likely also Japan shifting their supplier and customer base away from China, something that is not taking place today. It may also mean that countries such as India, Brazil, Russia and the CPTPP countries would need to choose sides, shifting their production and customer linkages toward either China or the U.S.

In this scenario, the U.S. would contest more forcefully for global economic leadership than it has in recent years. This would also likely require the U.S. to join or develop regional agreements, building on IPEF or joining CPTPP, or even reviving the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership—an abandoned trade agreement between the U.S. and EU.

De-dollarization—or a two-track system, with one dominated by the dollar and the other potentially dominated by another currency—could be a concern in this scenario.

This scenario could lead to lower productivity and inefficiencies as parts of the supply chains are duplicated on each side. Asymmetries in strengths in each grouping might lead to distortions— e.g., if one grouping has lower labor costs, and the other has a stronger innovation sector, the low abor cost grouping could have lower economic growth, and the innovation grouping could have higher inflation. The positive effects of this scenario may come from deeper trade integration among allied nations improving the flow of trade within the groupings.

Diversification

A third scenario could be a more measured diversification. A more diversified economic engagement profile could alleviate situations in which U.S. supply chains are excessively reliant on one geographic location—especially, but not exclusively, China.

Economically, this could lead to lower productivity, given the need for redundancy in systems and perhaps the loss of efficiency that comes from having multiple suppliers. Initial costs could be higher as firms need to navigate unfamiliar countries and systems. On the other hand, a shift away from using China as the default producer and shifting toward other EM countries with lower costs could be productivity enhancing, in addition to providing a more diversified supply chain

One shift that has already begun is building closer to the end user. Multinational companies both from China and the U.S. have opened or ramped up production at factories in Mexico to serve the U.S. market.17 This approach may be extended to more sectors over time.

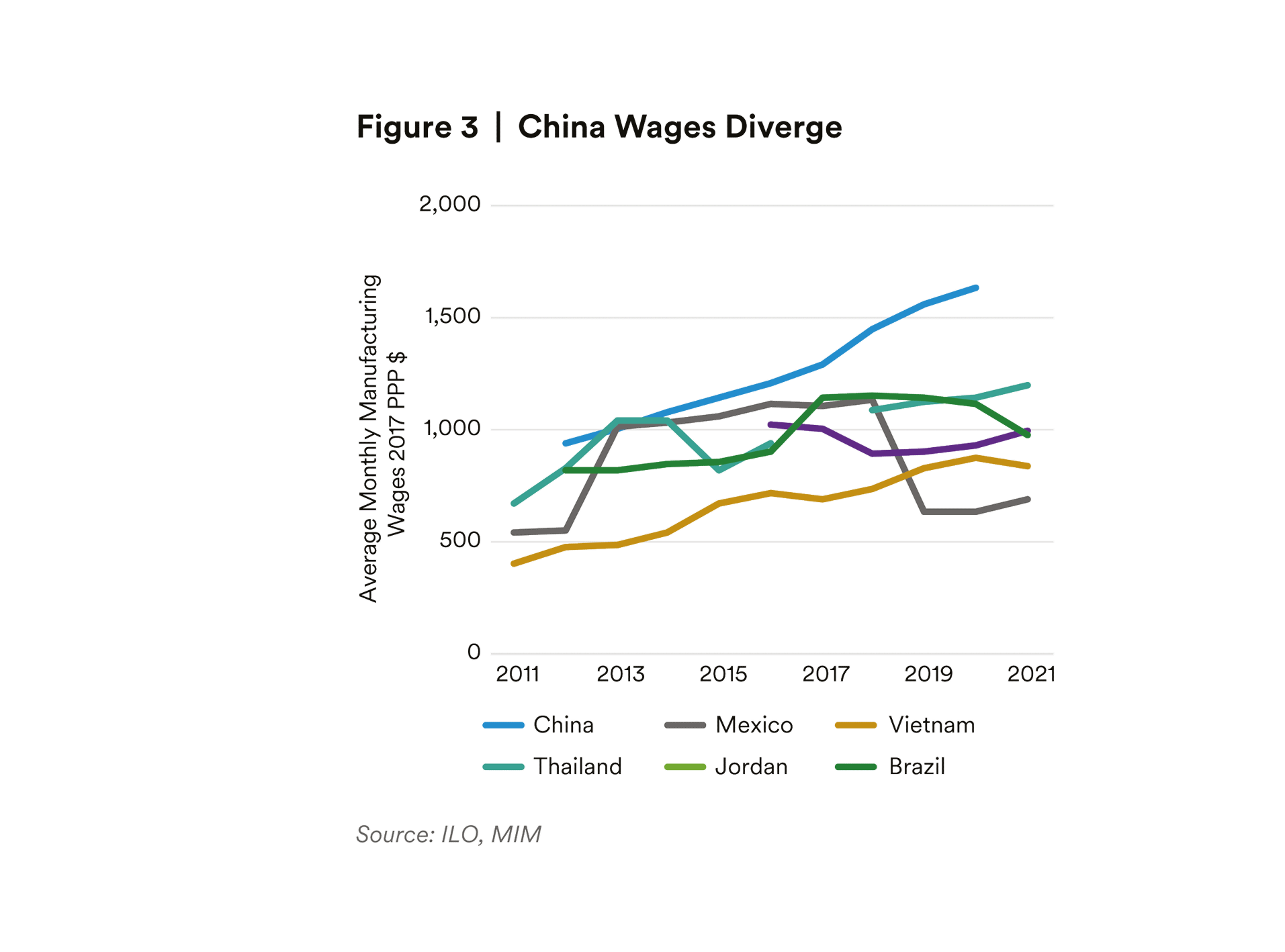

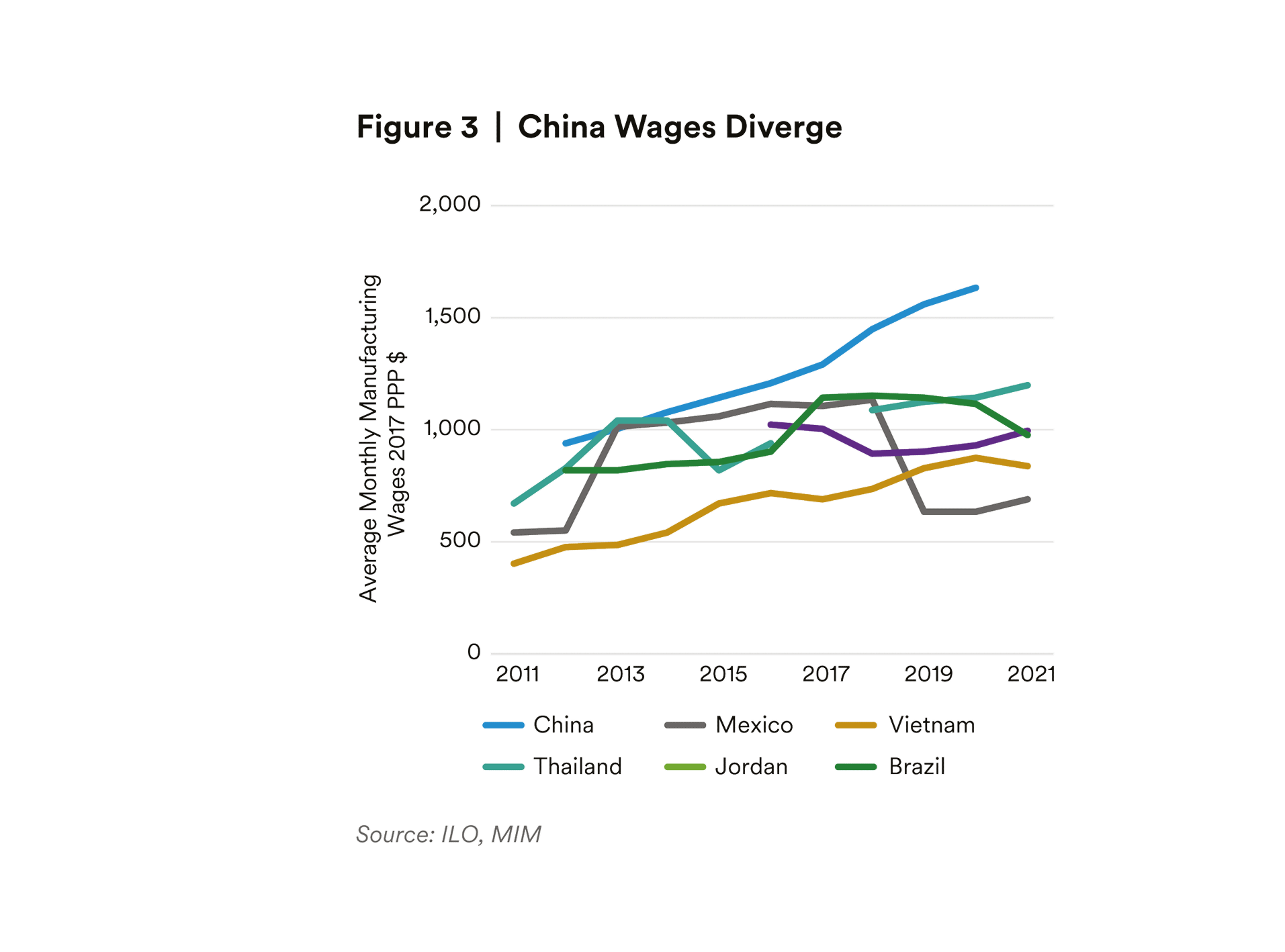

More generally, assumptions about the importance of being located in the Chinese market could be revisited. Chinese wages have risen over the last decade, and have diverged rapidly from other low- to middle-income countries in the last four years (Figure 3). Recalculating the cost of doing business, when including China’s relatively high wages and rising risks, may lead more companies to shift production or expand into other countries.

The EU would be unlikely to diversify significantly away from its reliance on China as a customer in the near term, particularly for its exports of industrial and capital goods. Their immediate need is to adjust their economy away from their ties to Russia. However, a diversification away from China could be feasible over time. Japan would similarly benefit from diversification from China as its largest import and export partner, but as with the EU, diversification would be challenging.

A more organic diversification could occur over time as trade shifts more toward trade in services, particularly digital trade. Digital trade has become increasingly viable as a substitute for goods trade or even for migration. A shift toward digital services could shift the locus of trade exports toward countries like India and the Philippines, and away from China.

China is likely to work hard to maintain a welcoming environment to multinational corporations and foreign investment. We expect China’s policy to increase its focus on newer technology sectors as a means of growth, suggesting a continued willingness to accommodate foreign technologybased investment.18

Conclusion

We believe that a new phase of globalization is beginning. Although it is still unclear whether disengagement, division or diversification—or some combination—will predominate in the long run, we believe the disengagement scenario will be the predominant theme in the near term.

First, national security and uncertain geopolitics have become more important to business planning than they have been in a long time—perhaps since September 11, 2001.

Second, resilience, including supply-chain resilience, is very likely to continue to matter. Although there may not be another global pandemic in our lifetime, we expect more shocks in the future. Aside from changes in geopolitical dynamics, climate change is likely to produce more shocks to the global economic system. Taking the lessons of the current shocks seriously is critical to future planning.

Third, the U.S. and China are currently behaving like rivals. Moreover, there are few strong voices, at least in the U.S., arguing for a more conciliatory approach, and policies that push back against China are currently one of the few, major bipartisan issues. More generally, the U.S. appears at best ambivalent about continuing to be a champion of the historic liberal trade order. It remains possible that the U.S. would disengage primarily from national security-related trade with China, while remaining engaged in other spheres, at least in the short run.

The above points make us particularly pessimistic about the diversification scenario, although it is likely the most positive economically. Instead, the U.S. appears to be choosing the disengagement scenario at the moment. The EU and Japan, with their ambivalent policies, appear hesitant to join the U.S. fully and embrace a division scenario, but may shift over the medium term if they see the need to do so.

A final point to note is that any changes to the global economic order are only one component of the resilience concerns that were raised by the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Not all vulnerabilities can be eliminated via localizing production. The U.S. toilet paper shortage at the beginning of the pandemic and supply problems with baby formula came about despite a mostly domestic production process. Europe faced its own localized supply-chain problems, with shipments via the Rhine River in greater jeopardy in recent years because of shifting weather patterns.19 Diversifying away from China—or from any other country—will not be enough to prevent future interdependence issues. Additional changes—inventory management, disaster management and production methods—aside from the globalization question, also need to be rethought.

Looking forward, we expect to pay particular attention to a number of markers that could help us determine globalization’s future path. The most obvious is to look at the U.S. and China, and their policies toward each other, and regional and multilateral organizations. Less obviously, we would look to increased tensions between the U.S., the EU and Japan, and how they are resolved. We would also look for any indicators of financial deintegration—whether de-dollarization or the further establishment of infrastructure that could enable a smoother de-dollarization in the long term. We would monitor changes in FDI flows and labor productivity as firms shift new investments around the globe. Finally, we would look to increased market fragmentation, and particularly, arguments around possibly diverging standards.

Endnotes

1OECD Trade Topics, “Regional trade agreements are evolving—why does it matter?” https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/regional-trade-agreements/

2 The Observatory of Economic Complexity | OEC - The Observatory of Economic Complexity.

3 Environmental provisions were strengthened over time, particularly for the USMCA. Congressional Research Service, “Environmental Provisions in Free Trade Agreements,” updated January 13, 2022. Labor unions including the AFL-CIO have generally opposed trade agreements, e.g., https://aflcio.org/sites/default/files/migrate/2009res_56.pdf

4 Alan Beattie and Frances Williams, “Doha trade talks collapse,” Financial Times, July 29, 2008.

5 The Economist, “Europe’s ambivalence over globalization veers toward scepticism,” October 20, 2022.

6 Three entered into force in 2012, having been negotiated and signed by 2008.

7 White House Presidential Archives, “Writing the Rules for 21st Century Trade,” February 18, 2015.

8 These included an investor-state dispute settlement mechanism that was weakened, and intellectual property rights protections that were narrowed, as well as fewer labor and environmental protections.

9 Shintaro Hamanaka, “Trans-Pacific Partnership Versus Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership: Control of Membership and Agenda Setting,” ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration No. 146, December 2014.

10 Ibid

11 See for example Eurasia Group, “Top Risks 2023,”; Borge Brende and Bob Sternfels, “Seizing the moment to build resilience for a future of sustainable inclusive growth,” McKinsey & Co., February 23, 2023; OECD Policy Responses, “The supply of critical raw materials endangered by Russia’s war on Ukraine,” August 4, 2022.

12 Guy Chazan and Patricia Nillson, “Germany confronts a broken business model,” Financial Times, December 6, 2022 and The Economist, “Germany faces a looming threat of deindustrialization,” September 11, 2022.

13 Yuka Hayashi and Vivian Salama, “Japan, Netherlands Agree to Limit Exports of Chip-Making Equipment to China,” The Wall Street Journal, January 28, 2023.

14 The Economist Intelligence Unit, “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework Falls Short,” May 25, 2022.

15 In recent years, European leaders have repeatedly expressed this sentiment despite escalating tensions between the U.S. and China: Silvia Amaro, “’China cannot be out, China must be in,’: France says it’s diverging with Washington on Beijing ties,” CNBC, January 20, 2023 and Esme Nicholson, “Why Western leaders are warily watching the German leader’s trip to China,” NPR, November 3, 2022.

16 The Economist Special Report: “The world divided,” October 15, 2022.

17 Why Chinese Companies Are Investing Billions in Mexico - The New York Times (nytimes.com)/ Mexico’s Industrial Hubs Grow as Part of Trade Shift Toward Nearshoring - WSJ

18 David Richter, “This Year’s Half-Hearted Policy Response a Harbinger for Things to Come,” MetLife Investment Management Investment Insights, October 12, 2022.

19 Joe Miller and Alexander Vladkov, “Rhine’s low water level blights German industry,” Financial Times, August 12, 2022.

Disclosure

This material is intended solely for Institutional Investors, Qualified Investors and Professional Investors. This analysis is not intended for distribution with Retail Investors.

This document has been prepared by MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”)1 solely for informational purposes and does not constitute a recommendation regarding any investments or the provision of any investment advice, or constitute or form part of any advertisement of, offer for sale or subscription of, solicitation or invitation of any offer or recommendation to purchase or subscribe for any securities or investment advisory services. The views expressed herein are solely those of MIM and do not necessarily reflect, nor are they necessarily consistent with, the views held by, or the forecasts utilized by, the entities within the MetLife enterprise that provide insurance products, annuities and employee benefit programs. The information and opinions presented or contained in this document are provided as of the date it was written. It should be understood that subsequent developments may materially affect the information contained in this document, which none of MIM, its affiliates, advisors or representatives are under an obligation to update, revise or affirm. It is not MIM’s intention to provide, and you may not rely on this document as providing, a recommendation with respect to any particular investment strategy or investment. Affiliates of MIM may perform services for, solicit business from, hold long or short positions in, or otherwise be interested in the investments (including derivatives) of any company mentioned herein. This document may contain forward-looking statements, as well as predictions, projections and forecasts of the economy or economic trends of the markets, which are not necessarily indicative of the future. Any or all forward-looking statements, as well as those included in any other material discussed at the presentation, may turn out to be wrong.

ll investments involve risks including the potential for loss of principle and past performance does not guarantee similar future results.

In the U.S. this document is communicated by MetLife Investment Management, LLC (MIM, LLC), a U.S. Securities Exchange Commission registered investment adviser. MIM, LLC is a subsidiary of MetLife, Inc. and part of MetLife Investment Management. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or that the SEC has endorsed the investment advisor.

This document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Limited (“MIML”), authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA reference number 623761), registered address 1 Angel Lane, 8th Floor, London, EC4R 3AB, United Kingdom. This document is approved by MIML as a financial promotion for distribution in the UK. This document is only intended for, and may only be distributed to, investors in the UK and EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (2014/65/EU), as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction, and the retained EU law version of the same in the UK.

For investors in the Middle East: This document is directed at and intended for institutional investors (as such term is defined in the various jurisdictions) only. The recipient of this document acknowledges that (1) no regulator or governmental authority in the Gulf Cooperation Council (“GCC”) or the Middle East has reviewed or approved this document or the substance contained within it, (2) this document is not for general circulation in the GCC or the Middle East and is provided on a confidential basis to the addressee only, (3) MetLife Investment Management is not licensed or regulated by any regulatory or governmental authority in the Middle East or the GCC, and (4) this document does not constitute or form part of any investment advice or solicitation of investment products in the GCC or Middle East or in any jurisdiction in which the provision of investment advice or any solicitation would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction (and this document is therefore not construed as such).

For investors in Japan: This document is being distributed by MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan) (“MAM”), 1-3 Kioicho, Chiyodaku, Tokyo 102-0094, Tokyo Garden Terrace KioiCho Kioi Tower 25F, a registered Financial Instruments Business Operator (“FIBO”) under the registration entry Director General of the Kanto Local Finance Bureau (FIBO) No. 2414.

For Investors in Hong Kong S.A.R.: This document is being issued by MetLife Investments Asia Limited (“MIAL”), a part of MIM, and it has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong (“SFC”). MIAL is licensed by the Securities and Futures Commission for Type 1 (dealing in securities), Type 4 (advising on securities) and Type 9 (asset management) regulated activities.

For investors in Australia: This information is distributed by MIM LLC and is intended for “wholesale clients” as defined in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act). MIM LLC exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services license under the Act in respect of the financial services it provides to Australian clients. MIM LLC is regulated by the SEC under US law, which is different from Australian law.

MIMEL: For investors in the EEA, this document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Europe Limited (“MIMEL”), authorised and regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland (registered number: C451684), registered address 20 on Hatch, Lower Hatch Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. This document is approved by MIMEL as marketing communications for the purposes of the EU Directive 2014/65/EU on markets in financial instruments (“MiFID II”). Where MIMEL does not have an applicable cross-border licence, this document is only intended for, and may only be distributed on request to, investors in the EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under MiFID II, as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction. The investment strategies described herein are directly managed by delegate investment manager affiliates of MIMEL. Unless otherwise stated, none of the authors of this article, interviewees or referenced individuals are directly contracted with MIMEL or are regulated in Ireland. Unless otherwise stated, any industry awards referenced herein relate to the awards of affiliates of MIMEL and not to awards of MIMEL.

1 MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”) is MetLife, Inc.’s institutional management business and the marketing name for subsidiaries of MetLife that provide investment management services to MetLife’s general account, separate accounts and/ or unaffiliated/third party investors, including: Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, MetLife Investment Management, LLC, MetLife Investment Management Limited, MetLife Investments Limited, MetLife Investments Asia Limited, MetLife Latin America Asesorias e Inversiones Limitada, MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan), and MIM I LLC and MetLife Investment Management Europe Limited.