Introduction

The past year capped off another decade of significant change in how institutional investors view the residential investment sector, and also signaled what is likely to come. Specifically, the single-family rental sector is following the same path toward institutional acceptance that apartments navigated in the 1990s and 2000s, and we believe this is being driven by two factors. First, demographic and secular shifts point toward a medium and long-term increase in demand for larger format rentals, such as single-family homes1 . Second, and perhaps more importantly, advances in information management platforms have made smaller investments accessible to investors with billion or trillion-dollar portfolios.

We believe the institutionalization of single-family rentals (SFR) which began in the early 2010s may near full maturity as an asset class by 2030. This could cause several things to occur. The most noticeable effect in the short term may be a compression in SFR yields as the market moves from small private investors who expect double digit levered returns, to institutional investors who may be comfortable with a higher single digit levered returns, due to both economies of scale and a lower average cost of capital. Yield compression could, in turn, put downward pressure on the homeownership rate as renting becomes more affordable relative to owning an equivalent quality home. This increase in the ratio of renters could translate into a larger investible universe for rental housing.

In the medium to long term, we believe the most significant effect of the institutionalization of SFR will be a rise in popularity of master planned rental communities, as opposed to traditional construction of more disparate homes or neighborhoods built for owner-occupiers. To understand where the SFR investment sector is headed, we believe it is important to first understand the history and current state of the more established rental apartment sector.

A Brief History of Housing

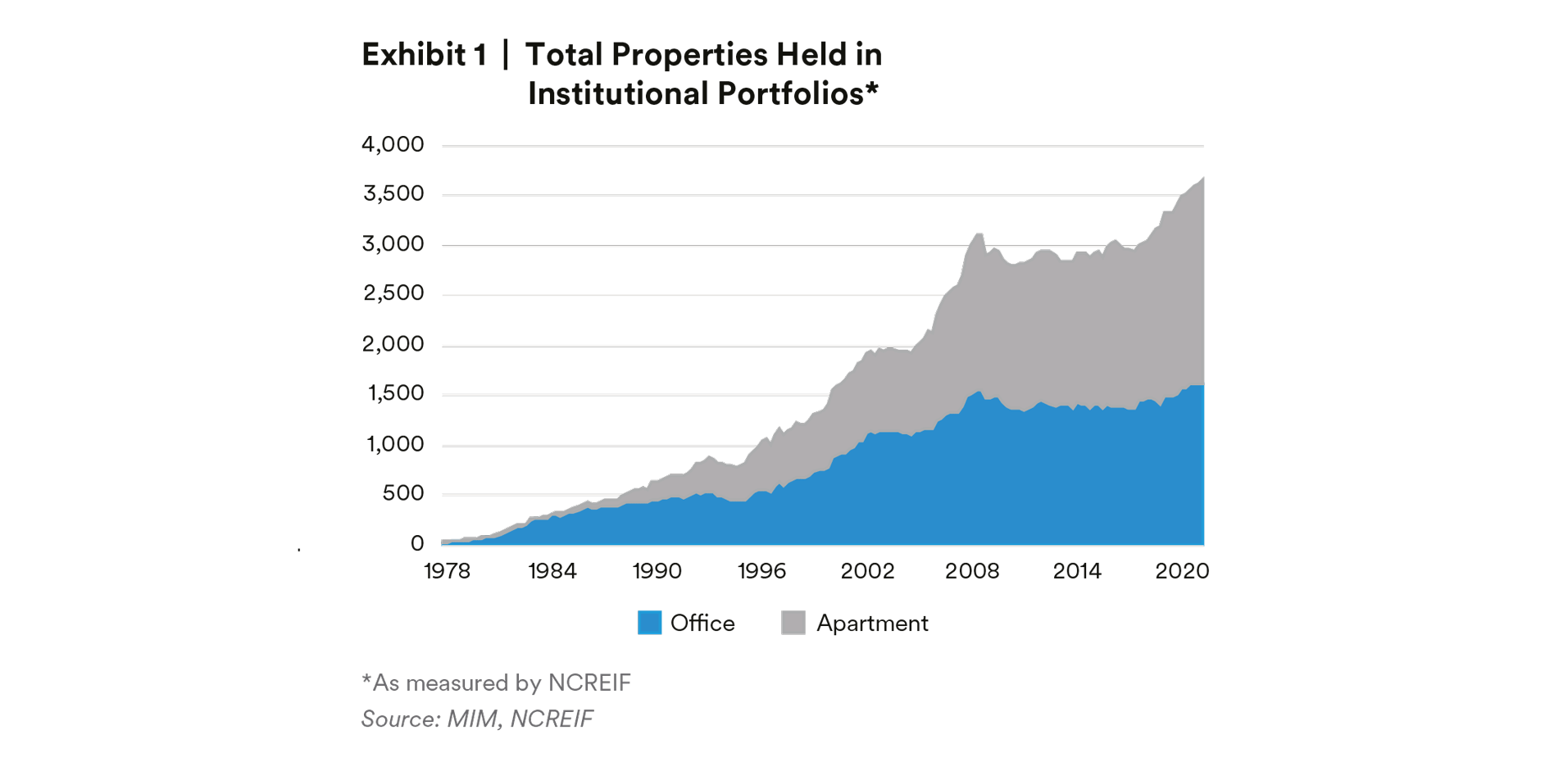

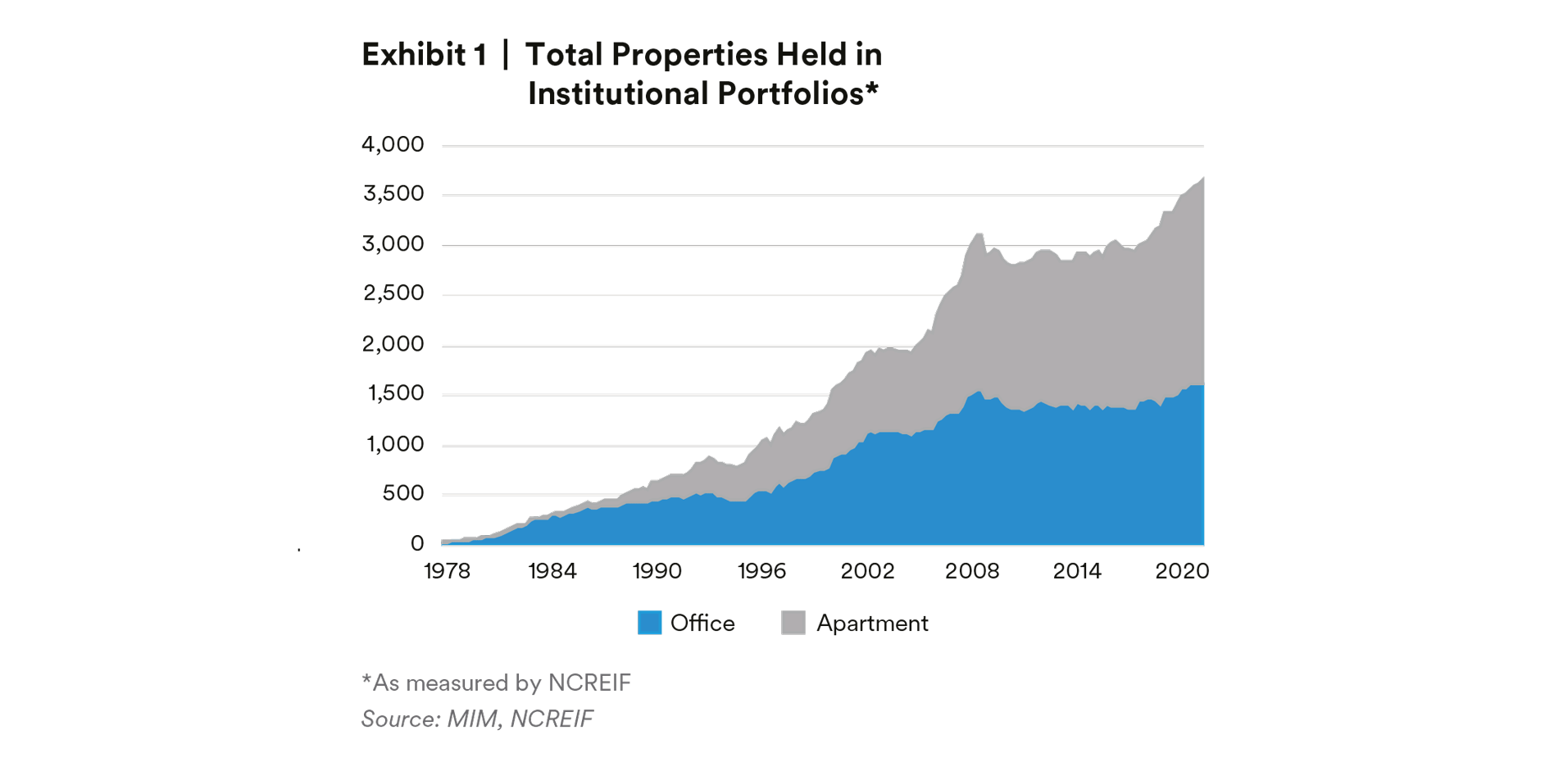

Institutions have been investing in apartments for a relatively short period of time. Although some large institutions (such as MetLife) can date their ownership and management of apartments to over 50 years ago, the sector wasn’t fully embraced by institutions until the years following the savings & loan crisis in the early 1990s. In 1980, for instance, the nascent National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF) tracked the performance of just 9 apartment properties (4% of the NCREIF Property Index at the time), compared to a broader set of 80 office properties (30% of the NCREIF Property Index at the time), whereas today the two asset classes are closer to equal representation in the NPI (see exhibit 1).

Before the 1990s, institutional investing in the apartment sector was challenging due to a lack of transparency, the need for large staffs, and a lack of reliable and regionally scaled property managers. At the time, reporting standards from NCREIF, as well as early publicly listed REITs, gave investors only a basic level of transparency. As investment track records lengthened and national property management firms were formed and consolidated, more capital was allocated to the apartment sector. This resulted in lower required yields by investors, and the risk premium ascribed by investors relative to the earlier-to-institutionalize office sector also evolved. Between 1985 and 1995, apartment yields traded 50 bps above office assets. Over the subsequent decade apartment yields traded on average 70 bps below office yields.2

By the early 2000’s, the institutionalization of the apartment sector advanced to include a broadening of investible cities. Initially, markets like New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco had a critical mass of liquidity and transparency, and captured a majority share of capital. Since that time, investors slowly but steadily increased their apartment allocations in markets like Austin, Denver, and even smaller markets like Raleigh and Salt Lake City. In 2021, institutional investors have a notable presence in more than 50 U.S. cities, versus a concentration in around 3-5 cities in the 80’s and 90’s.3

We believe the next stage of institutionalization of residential real estate investing is a broadening of rental property types to include single-family homes.

Residential Rebirth

Following the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, a small number of institutions believed depressed home prices created an opportunity in the SFR sector. Institutional investors, however, had few direct paths to owning equity in single-family homes. Much like apartment investing in the 1980s and earlier, investing in single-family homes as rentals was challenging. However, improvements in software and the ability to scale property management companies have made the SFR space easier to access in a relatively short amount of time.

In terms of transparency, the public REIT sector now offers investors around a decade of performance history for SFR. In addition, a growing number of specialized data vendors have been collecting and reporting on information that allows investors to understand market conditions and more consistently underwrite opportunities. Lastly, in 2021, the NCREIF Research Committee created a Single Family Rental Task Force that has been tasked with evaluating how to categorize and benchmark the sector4.

Based on our view of the volatility of historical returns, and our outlook for demand and supply growth that we will discuss next, we believe single family rental yields should be slightly below apartment yields. In practice, however, we estimate that single asset single family rentals are trading at a 5.5% cap rate, and portfolios are trading at a 4.5% cap rate. Built-for-rent communities, which represent a very small share of the single family renal investible universe and are thinly traded, may be trading with return expectations that are on par, or slightly below, where apartment assets are trading.5

The investable universe is large and growing, which will provide institutional investors with the ability to achieve meaningful portfolio allocations to the sector.

Near Term Prospects

Residential investors enjoyed a strong year in 2021, despite mixed macroeconomic pressures. In our view, there are cyclical and structural conditions exerting price pressure on U.S. housing.

Examples of temporary / cyclical COVID-related conditions include factors that limited housing supply last year, such as seniors remaining in their homes rather than moving into group facilities, thus reducing the supply of existing single-family houses for sale. Supply was also limited through September 2021 by eviction and foreclosure moratoriums. We expect these conditions to abate in 2022 and 2023, which should modestly ease inflationary pressures in residential real estate markets.

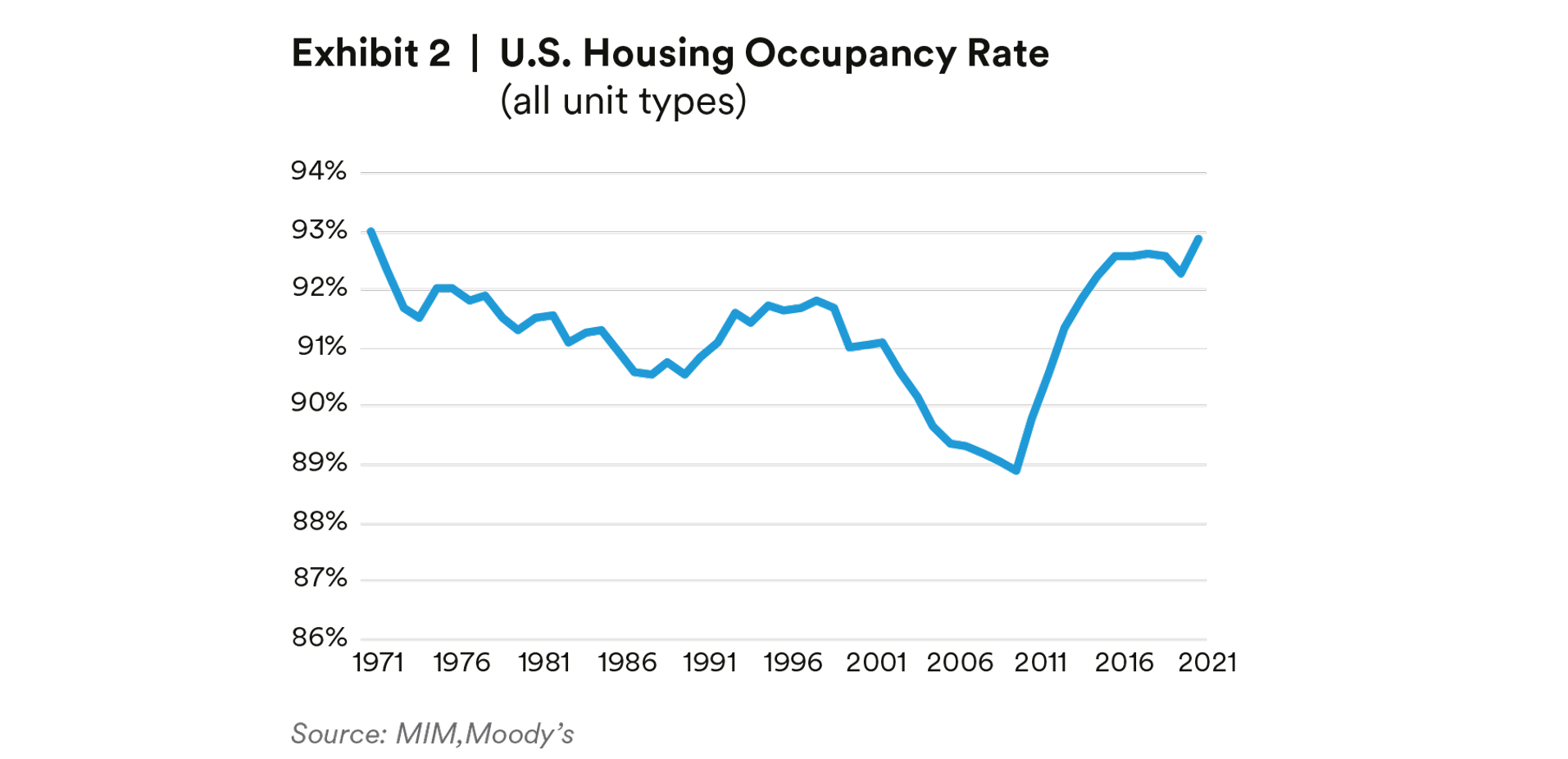

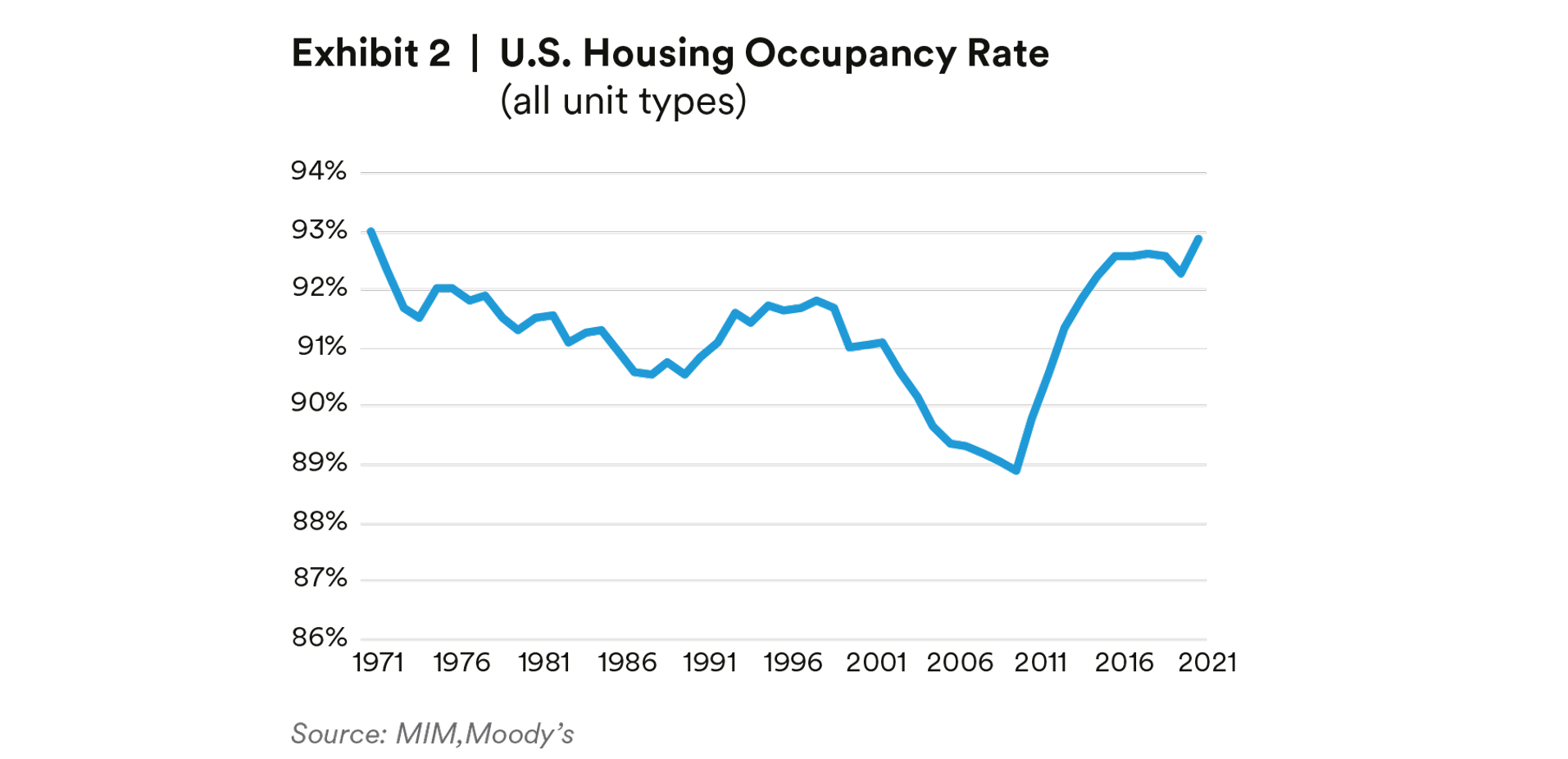

There are, though, longer-term structural factors that have led rents and home prices to outpace wage growth in recent years. On the supply side, new construction was low last decade. The U.S. housing stock increased by just 0.3% per year from 2010-2020 versus a 1.4% average annual increase in each of the 3 prior decades.6 At the same time, population growth and household formation progressed at a steady pace, driving housing occupancy (the number of housing units per U.S. household) to the highest level since the 1970’s (exhibit 2).

Additionally, low interest rates have kept monthly mortgage payments relatively low for would-be home buyers, driving down for-sale home inventory and driving up prices. This had a secondary effect on rents, and could help support fundamentals even as some of the temporary COVID-related factors mentioned above reverse.

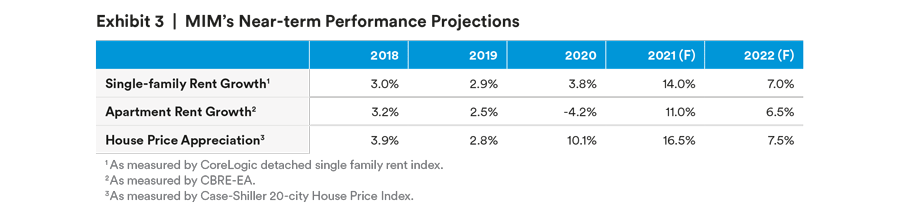

Taken together, we believe home price appreciation, apartment rent growth, and single-family housing rent growth will remain elevated, but could moderate somewhat as the cyclical conditions mentioned above begin to dissipate next year.

With an understanding of current conditions and how rents and home prices might respond next year, we turn our attention to understanding the rest of this decade.

Underwriting the Outlook

In our view, population growth is one of the most straightforward metrics to forecast. We know how many people were born every year, how long they will likely live on average, and precisely how long it will take them to reach every age bracket.

We also have relatively high confidence in projecting the rate at which individuals of various age groups will form households, and what type of housing those households may want to live in.7

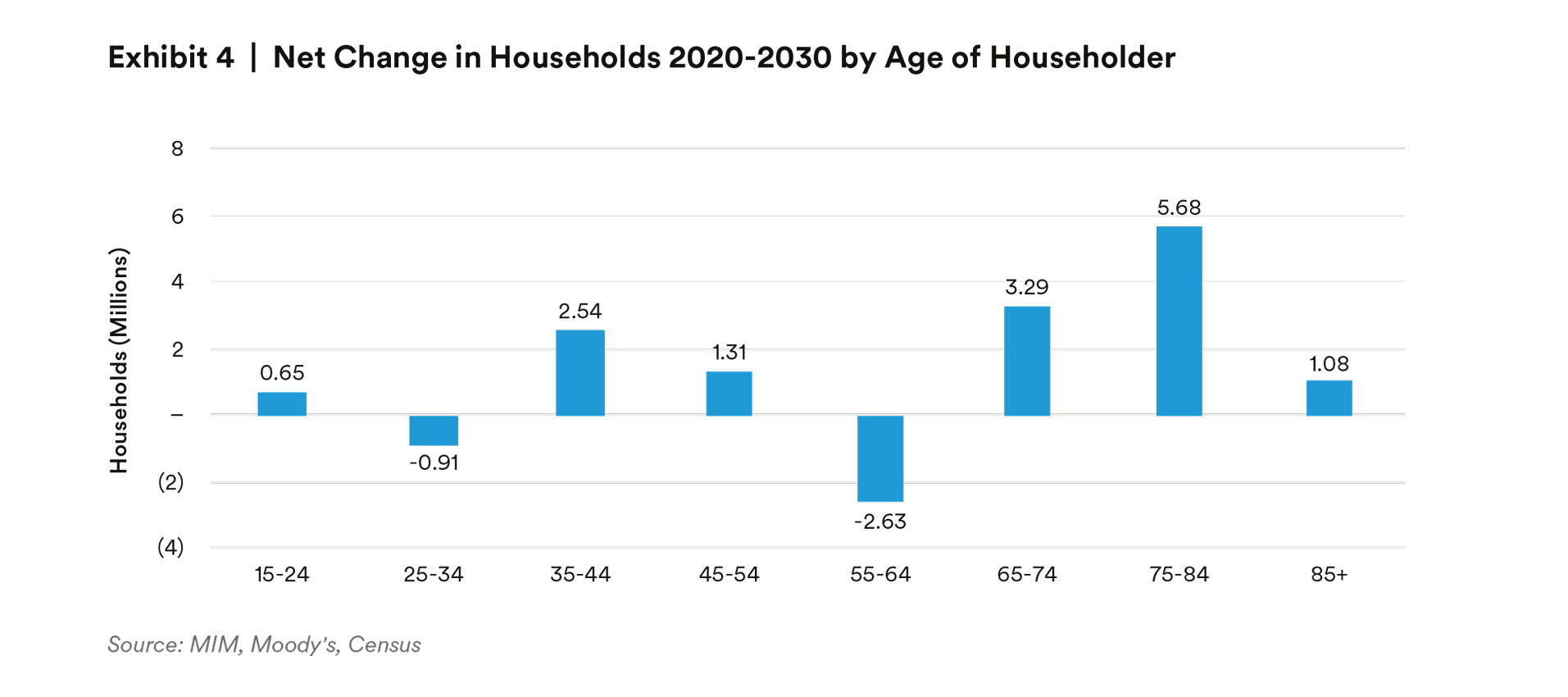

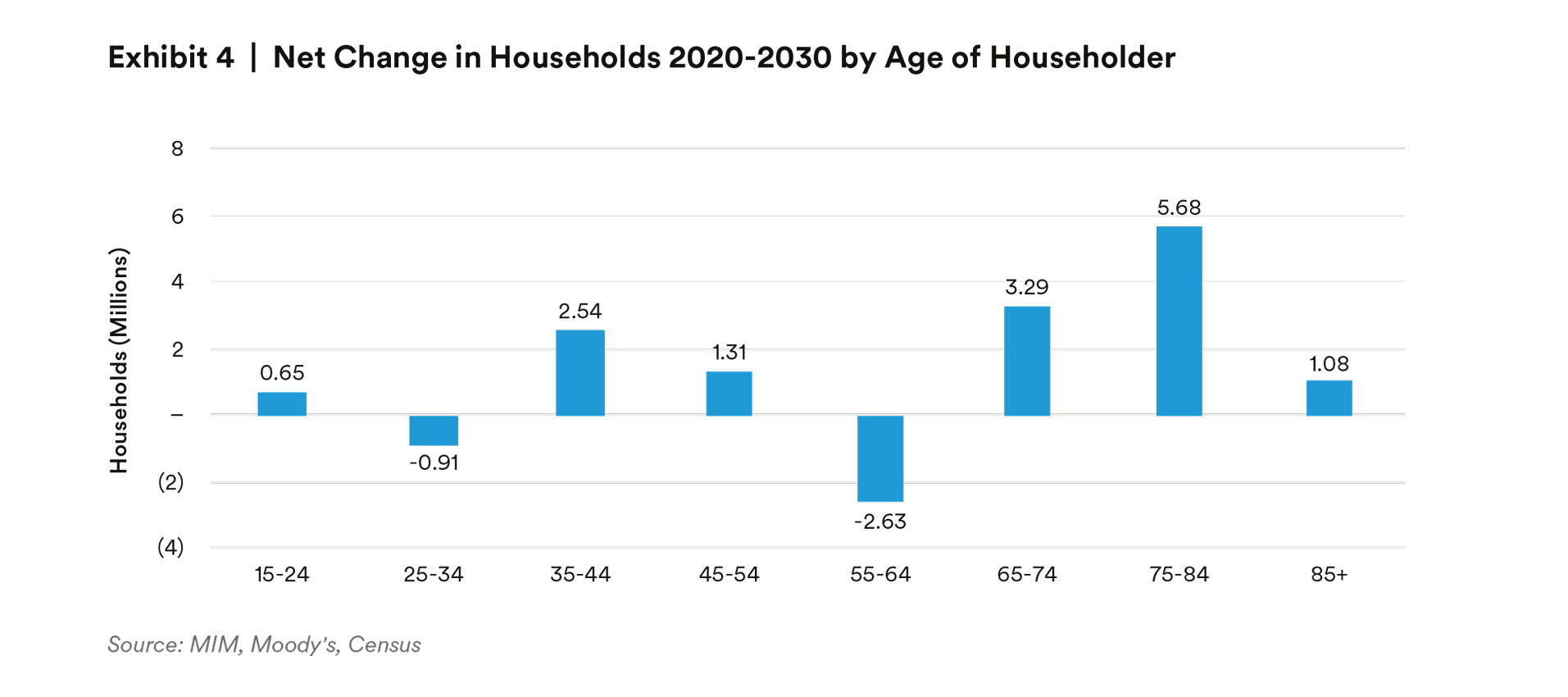

In total, we believe 11 million new households will be formed in the U.S. over the next decade, although this number could shift up or down depending on how housing costs shift.

If housing costs (including home prices, mortgage rates, and rents) significantly exceed income growth, we could expect lower household formation. For example, young people may choose to “double up” with parents or roommates at a higher rate.

The Three Categories of New Renters

Households entering child rearing years, office workers needing more space to occasionally work-from-home, and aging Baby Boomers, are the three categories that will exert the strongest demand pressure on the residential investment market over the next decade, in our view. We believe these groups will demand a similar form of housing, namely 2-3 bedroom units in the 1,000-2,000 square foot range. But why rentals, and why not for-sale housing?

Aging Millennials and Baby Boomers are both facing their own versions of financial challenges. Millennials continue to contend with elevated student debt burdens and lack of savings. The median student loan debt among home buyers aged 31-40 is $33,000, and nearly 70% of homebuyers say debt is delaying homeownership. At the same time, we estimate the average down payment requirement has nearly doubled between 2010 and 2020.8 This suggests Millennials may continue to rent for longer than prior generations.

On the other end of the population range, Baby Boomers (who will account for a large share of net household formation in the 2020s) are contending with concerns over social security, changes to (and challenges with) pension systems, and lower savings rates, while medical and other household expenses have risen.9 Uncertainty about their standard of living in retirement has partially driven a rise in rentership among the older generation, who may use home equity to unlock retirement funds.

Although it was difficult to foresee the demand increase resulting from the pandemic and work-from-home space needs, the wave of millennials becoming parents and aging Baby Boomers was not. In our 2016 whitepaper, Echoing the Boom, we argued investors should begin focusing on larger format housing, including SFR, and that this type of housing could generate the lion’s share of new rental demand during the 2020’s. We continue to believe that to be the case today, but with an added boost of single and non-child household seeking more space.

Supply of new housing

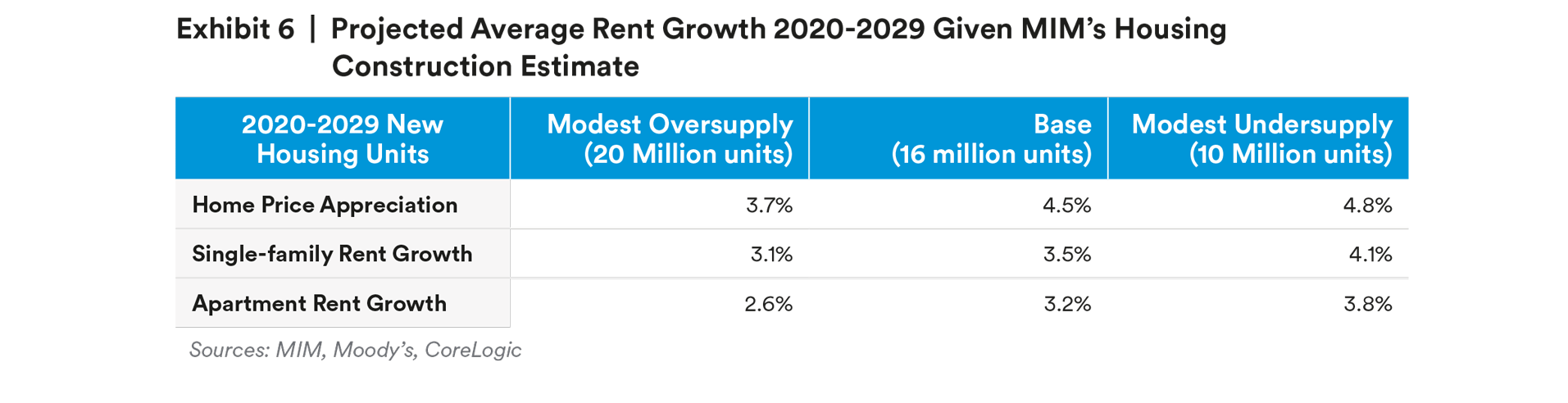

Although we believe 11 million new households will be formed over the next decade, that is only part of the story. The evolving supply of housing units is another factor, and supply does not simply mean new construction. Based on a number of factors, including the number of homes that were built before 1950 that are now reaching obsolesce, we estimate 4.5 million apartment units or single-family homes will be demolished during the 2020s (negative supply growth). Marrying this with the 11 million household formations implies there will be demand for a minimum of 15.5 million new housing units during the decade in our view.

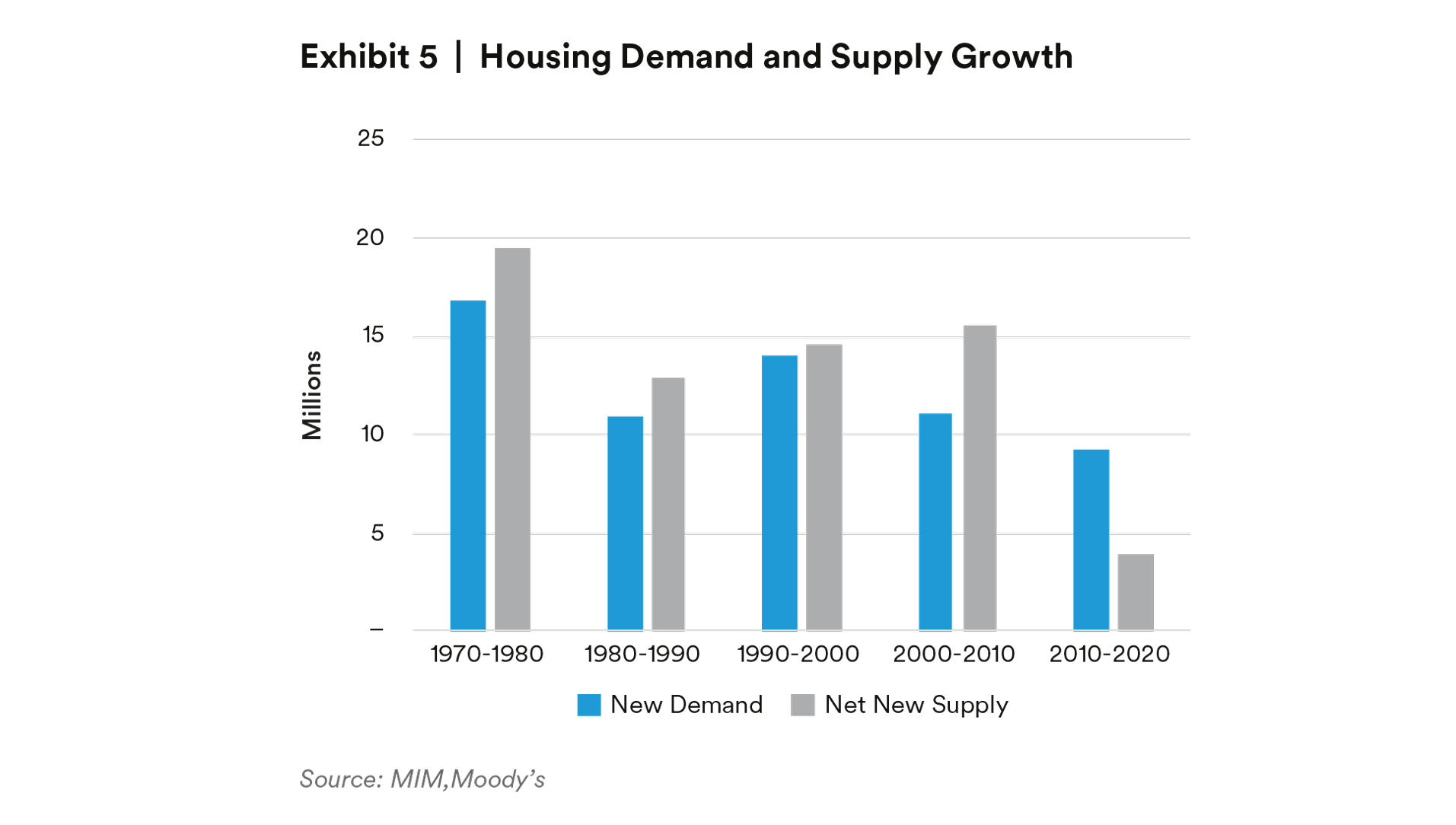

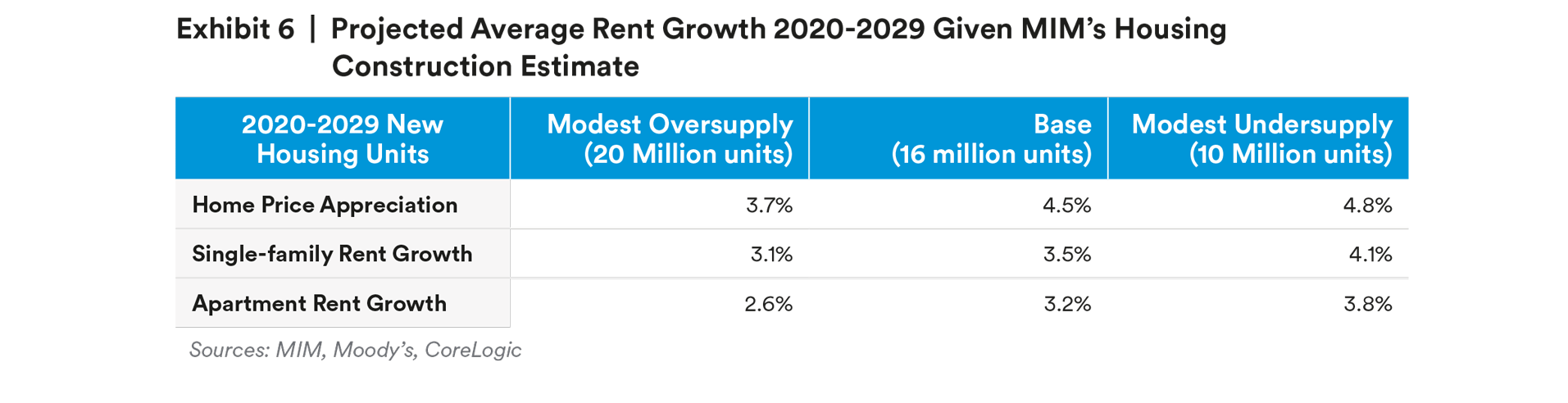

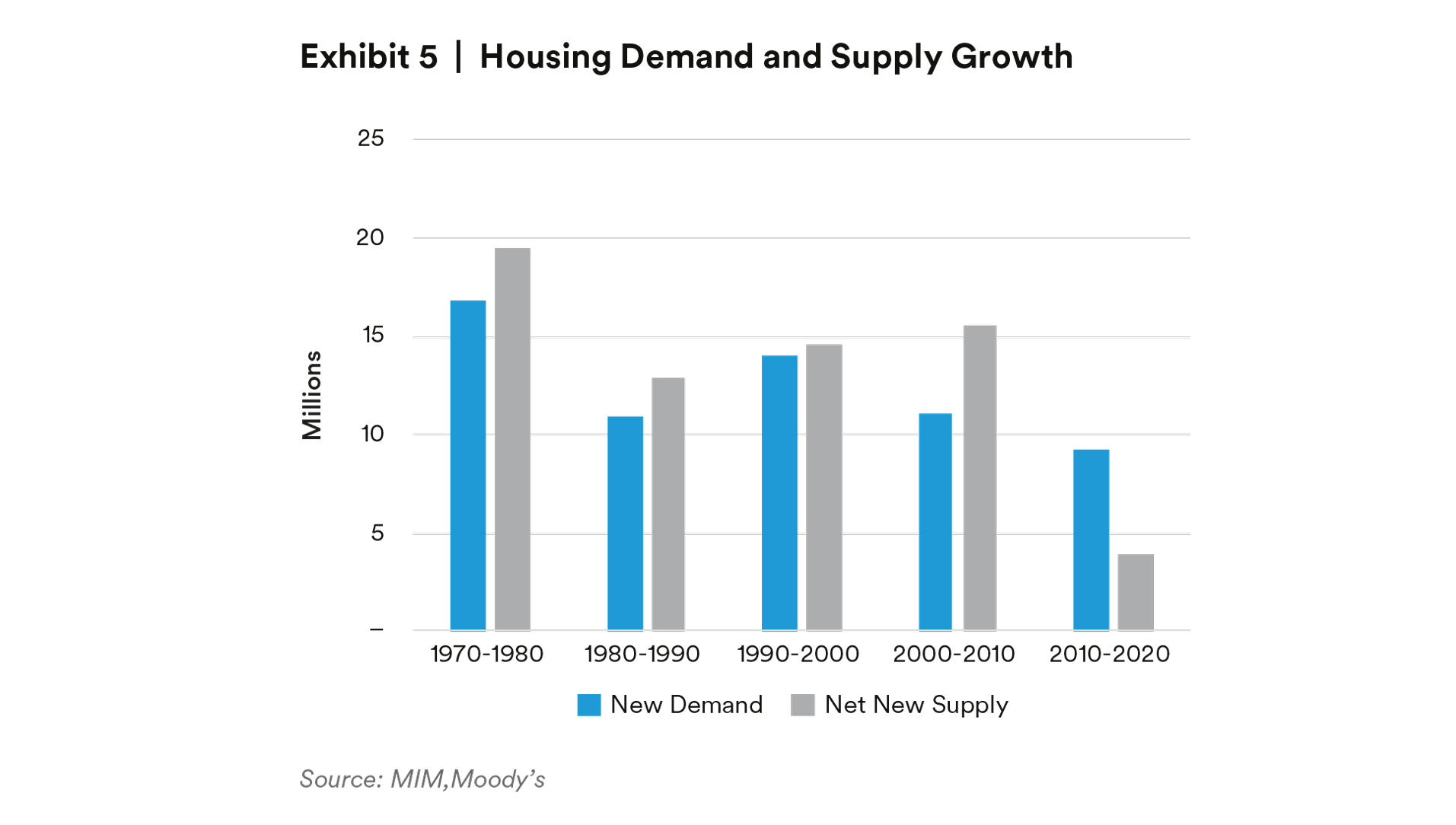

Adding nearly 16 million housing units, or 11 million units net of demolitions, would meaningfully outpace the 2010-2020 decade, when only 3.9 million net new housing units were delivered. We believe this base case expectation reflects the realities that define the current housing market.

Getting to 16 Million

As exhibit 5 shows, residential supply and demand have not historically been as disconnected as was the case over the last 20 years. While labor and zoning constraints have hindered supply in the last decade, we believe a declining cost of capital for single-family home construction (as outlined above), rising prices for virtually all residential formats, and a legislative environment increasingly concerned with housing affordability could change these conditions. For example, in August 2021 California lawmakers passed Senate Bill 9, also called the “Duplex Bill,” which will allow two-unit buildings on land previously reserved for single-family detached homes.10 We expect to see more legislation across the country at the state and local level that will be intended to spur new housing construction, especially in areas where housing affordability issues are the most acute.

Based on an analysis of historical housing construction, we believe around 80% of the new construction over the next decade will be single-family homes, and 20% will be apartments. This differs from the most recent decade when 40% of new housing supply was apartment construction.

If more than 16 million units are built, then we would expect housing costs (both rent and purchase price) to grow at, or slightly below, the rate of inflation later this decade, while we believe construction of fewer than 16 million housing units would result in above-inflationary growth.

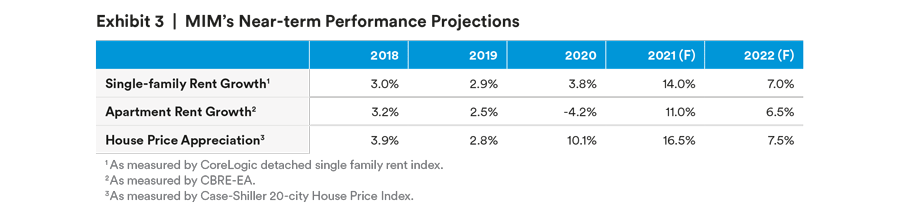

In the very near term, labor and material shortages suggest the residential market may struggle to achieve 1.6 million units of new construction per year (though housing starts have been accelerating of late). As a result, and as outlined in exhibit 3, we believe rent and home price appreciation will be elevated in 2022. As supply growth accelerates, we expect home price appreciation, apartment rent growth, and single-family rent growth to moderate. Additionally, we expect supply and demand for traditional apartments to more quickly reach equilibrium given the slightly less favorable, though still positive, demographic conditions for traditional apartments. As a result, apartment rent growth may modestly trail single-family home price and rent growth in the 2020’s.

We believe there is more risk that housing will be undersupplied this decade, rather than oversupplied. The labor and zoning constraints mentioned may continue to create structural challenges. For example, a decline in immigration and an increase in college education rates have both subtracted from the availability of construction labor. Additionally, the recently passed $1 trillion infrastructure package may further crowd out construction labor later this decade.

Diversification Within the Single-family Rental Sector

While SFR offers investors an additional source of portfolio diversification relative to apartments or the broader commercial real estate asset class, there are a variety of investment options within the SFR sector that are worth outlining.

“Scattered home” strategies typically involve acquiring many disparate existing single family homes across a variety of metropolitan areas. This was one of the earliest and most common forms of institutional investment in the single family rental sector.

“Purpose-built” strategies involve investing in contiguous communities of single family homes that are built for rent. Home sites in purpose-built communities may be attached / higher density, and may closely resemble 1-story garden apartments. They may also be detached, low-density sites. The purpose-built category is in its very early days, but we estimate these communities may operate with lower operating expense and capital expenditure ratios and may trade at a yields below scattered home investments.

We believe both classes of single family rentals offer attractive investment opportunities today. The need for new housing stock provides an opportunity for developers of purpose-built product, while existing scattered home stock, though older, may in some cases offer more “infill” locations closer to employment centers and transportation links.

Risks to the Outlook

We believe the most apparent upside risks for the single family rental sector include an even faster institutionalization that drives cap and discount rates down more quickly than we are expecting, an increase in “NIMBYism” that causes more severe supply shortages, and an uptick in “work from home” that incentivizes households to prioritize living in a larger dwelling.

The most apparent downside risks may include a misunderstanding of the reasons single family home prices have appreciated so much since the start of the pandemic, a more significant downsizing effect from the baby boomer generation (such as individuals moving into retirement facilities at a faster pace) which greatly increases the supply of housing on the market, and a full reversal in work-from-home trends that causes many recent home buyers to downsize to smaller apartments. Additionally, the for-sale housing market has been a politically sensitive topic for over a century, and legislative changes that can impact investor returns are difficult to predict. Increasing legislation in the single family rental space could slow the pace of institutionalization, and could potentially disrupt the balance between supply and demand.

Conclusion

With consideration of these risks, we believe the outlook for the residential sector, including both apartments and single family homes, is positive. We believe ground-up development and build-to-core opportunities are worth exploring in the SFR space, particularly in light of tight housing market conditions today as well as demographic shifts pointing toward resilient demand for this asset type.11 Our outlook for the balance between supply and demand in the traditional apartment sector remains positive, even for studio and CBD apartments. Although we feel demographics may be less favorable for these categories, land, labor, and materials for new residential construction will likely be directed away from these formats, allowing for stable vacancies and rent growth during the decade.

Endnotes

1 Demographic shifts from millennials who age into parenthood and want more space to raise children. Secular shifts from office workers who need more space to occasionally work from home.

2 NCREIF, 3Q 2021.

3 NCREIF, 3Q 2021.

4 The committee is chaired by Michael Steinberg of MetLife Investment Management

5 Based on analysis of Green Street data, as well as consideration of limited transaction data made available by SFR REITs, and transactions that MIM has considered.

6 Moody’s, November 2021.

7 Census, November 2021.

8 MIM, National Association of Realtors. November 2021.

9 Boomer Expectations for Retirement, Insured Retirement Institute. 2019.

10 California State Senate, 2021.

11 NCREIF, 3Q 2021.

Disclosures

This material is intended solely for Institutional Investors, Qualified Investors and Professional Investors. This analysis is not intended for distribution with Retail Investors.

This document has been prepared by MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”)1 solely for informational purposes and does not constitute a recommendation regarding any investments or the provision of any investment advice, or constitute or form part of any advertisement of, offer for sale or subscription of, solicitation or invitation of any offer or recommendation to purchase or subscribe for any securities or investment advisory services. The views expressed herein are solely those of MIM and do not necessarily reflect, nor are they necessarily consistent with, the views held by, or the forecasts utilized by, the entities within the MetLife enterprise that provide insurance products, annuities and employee benefit programs. The information and opinions presented or contained in this document are provided as of the date it was written. It should be understood that subsequent developments may materially affect the information contained in this document, which none of MIM, its affiliates, advisors or representatives are under an obligation to update, revise or affirm. It is not MIM’s intention to provide, and you may not rely on this document as providing, a recommendation with respect to any particular investment strategy or investment. Affiliates of MIM may perform services for, solicit business from, hold long or short positions in, or otherwise be interested in the investments (including derivatives) of any company mentioned herein. This document may contain forward-looking statements, as well as predictions, projections and forecasts of the economy or economic trends of the markets, which are not necessarily indicative of the future. Any or all forward-looking statements, as well as those included in any other material discussed at the presentation, may turn out to be wrong.

All investments involve risks including the potential for loss of principle and past performance does not guarantee similar future results. Property is a specialist sector that may be less liquid and produce more volatile performance than an investment in other investment sectors. The value of capital and income will fluctuate as property values and rental income rise and fall. The valuation of property is generally a matter of the valuers’ opinion rather than fact. The amount raised when a property is sold may be less than the valuation. Furthermore, certain investments in mortgages, real estate or non-publicly traded securities and private debt instruments have a limited number of potential purchasers and sellers. This factor may have the effect of limiting the availability of these investments for purchase and may also limit the ability to sell such investments at their fair market value in response to changes in the economy or the financial markets

In the U.S. this document is communicated by MetLife Investment Management, LLC (MIM, LLC), a U.S. Securities Exchange Commission registered investment adviser. MIM, LLC is a subsidiary of MetLife, Inc. and part of MetLife Investment Management. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or that the SEC has endorsed the investment advisor.

This document is being distributed by MetLife Investment Management Limited (“MIML”), authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA reference number 623761), registered address Level 34 One Canada Square London E14 5AA United Kingdom. This document is approved by MIML as a financial promotion for distribution in the UK. This document is only intended for, and may only be distributed to, investors in the UK and EEA who qualify as a “professional client” as defined under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (2014/65/EU), as implemented in the relevant EEA jurisdiction, and the retained EU law version of the same in the UK.

For investors in the Middle East: This document is directed at and intended for institutional investors (as such term is defined in the various jurisdictions) only. The recipient of this document acknowledges that (1) no regulator or governmental authority in the Gulf Cooperation Council (“GCC”) or the Middle East has reviewed or approved this document or the substance contained within it, (2) this document is not for general circulation in the GCC or the Middle East and is provided on a confidential basis to the addressee only, (3) MetLife Investment Management is not licensed or regulated by any regulatory or governmental authority in the Middle East or the GCC, and (4) this document does not constitute or form part of any investment advice or solicitation of investment products in the GCC or Middle East or in any jurisdiction in which the provision of investment advice or any solicitation would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction (and this document is therefore not construed as such).

For investors in Japan: This document is being distributed by MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan) (“MAM”), 1-3 Kioicho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0094, Tokyo Garden Terrace KioiCho Kioi Tower 25F, a registered Financial Instruments Business Operator (“FIBO”) under the registration entry Director General of the Kanto Local Finance Bureau (FIBO) No. 2414.

For Investors in Hong Kong: This document is being issued by MetLife Investments Asia Limited (“MIAL”), a part of MIM, and it has not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong (“SFC”).

For investors in Australia: This information is distributed by MIM LLC and is intended for “wholesale clients” as defined in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act). MIM LLC exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services license under the Act in respect of the financial services it provides to Australian clients. MIM LLC is regulated by the SEC under US law, which is different from Australian law.

1 MetLife Investment Management (“MIM”) is MetLife, Inc.’s institutional management business and the marketing name for subsidiaries of MetLife that provide investment management services to MetLife’s general account, separate accounts and/ or unaffiliated/third party investors, including: Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, MetLife Investment Management, LLC, MetLife Investment Management Limited, MetLife Investments Limited, MetLife Investments Asia Limited, MetLife Latin America Asesorias e Inversiones Limitada, MetLife Asset Management Corp. (Japan), and MIM I LLC.